Presidents and the Constitution

40 LessonsHow is this resource organized?

- Volume I features fifteen lessons organized according to five constitutional themes: “The President and Federal Power;” “War and the Constitution,” “Slavery and the Constitution,” “The President as Chief Diplomat,” and “Electing the President.”

- Volume II features three new themes and additional lessons on “The President and Federal Power” and “War and the Constitution.”

- Each theme begins with a scholarly essay, discussing the constitutional theme and placing the issues in their historical context. Following the essay is a primary source analysis, called “Constitutional Connection”, which can serve as an introductory activity for the lessons in the theme.

- Each them contains three individual lessons on three Presidents.

- Lessons can be approached and presented individually, historically, or thematically. Each lesson includes a historical narrative about the featured President, focusing on the constitutional issues during their tenure in office.

- Lessons are modular and include warm-up activities, primary source analyses, simulations, guided controversies, role-plays, and other hands-on activities.

Want to create your own playlists, save resources to your library, and access answer keys? Sign up for an educator account!

2 Units

Unit

UnitPresidents and the Constitution Volume 1

Presidents and the Constitution will help you engage your students in this debate by analyzing the actions of Presidents in light of the Constitution.

Unit

UnitPresidents and the Constitution Volume 2

Presidents and the Constitution will help you engage your students in this debate by analyzing the actions of Presidents in light of the Constitution.

40 Lessons

Lesson

LessonAbraham Lincoln and Habeas Corpus

The “Great Writ” or habeas corpus has been an essential civil liberty guaranteed since Magna Carta. In listing powers denied to Congress, the Constitution notes that “The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” In 1861, Abraham Lincoln invoked this power of Congress—which was not in session—to suspend habeas corpus in certain areas. The next year, as he believed the civil justice system was inadequate to deal with the rebellion, he expanded the suspension throughout the United States and established military tribunals to try citizens charged with disloyalty. In this lesson, students explore Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus and constitutional issues surrounding it.

Lesson

LessonAbraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation

Presidents Buchanan, Lincoln, and Johnson believed that the Constitution protected the institution of slavery. Lincoln came to the conclusion that, in order to preserve the Constitution and the Union it created, he must apply a new understanding of the principles on which the nation was built. The time had come to bring the nation’s policies in line with the of the Declaration of Independence that “…all men are created equal…” In this lesson, students will analyze Abraham Lincoln’s views on slavery and the Constitution as evidenced in the Emancipation Proclamation.

Lesson

LessonAndrew Jackson and Indian Removal

Andrew Jackson pursued a policy of removing Native Americans from lands in the east to new territories west of the Mississippi. Removal was popular, as it would result in the opening of hundreds of thousands of acres to white settlement and gold mining. Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, a federal law that empowered the President to negotiate treaties with Indian tribes with the goal of moving them west. Legislation designed to force Native Americans out was also passed at the state level. When Georgia ignored an 1831 Supreme Court ruling that state laws had no force against Indian tribes, Jackson turned a blind eye. Neither Jackson nor the US Senate listened when the Cherokee objected that the Treaty of New Echota was fraudulent. Jackson’s decisions regarding the enforcement of removal laws against Native Americans set the stage for the Trail of Tears, one of the most dishonorable events in American history.

Lesson

LessonAndrew Johnson and the Civil War Amendments

President Andrew Johnson saw himself as a protector of the United States Constitution during and after the Civil War. In his efforts to preserve and restore the Union, he supported the Thirteenth Amendment ending slavery. The same motive led him to oppose the Fourteenth Amendment because he believed it would infringe on the legitimate powers of the states. In this lesson, students analyze Johnson’s leadership with respect to Reconstruction, and specifically his response to the passage of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: Electing the President

How the Constitution talk about presidential elections?

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: Impeachment and the Constitution

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution allows for impeachment of the President.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: Presidents and the Transfer of Power

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution effects the transfer of power between presidents.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: Slavery and the Constitution

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution relates to the institution of slavery.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: The President and Federal Power (V1)

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution lays out the President's powers.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: The President and Federal Power (V2)

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution bestows federal power to the President.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: The President as Chief Diplomat

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution describes the President as Chief Diplomat.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: The President as Enforcer of the Law

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution allows the President to enforce the law.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: War and the Constitution (V1)

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution lays out the President's powers.

Lesson

LessonConstitutional Connection: War and the Constitution (V2)

This lesson allows students to analyze the Constitution and ask questions about how the Constitution lays out the President's powers.

Lesson

LessonDwight D. Eisenhower and the Little Rock Crisis

The Supreme Court case of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), with its declaration that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, overturned decades of precedent and challenged deeply-held social traditions. Southern resistance to the decision was widespread. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was not enthusiastic about federal judicial intervention in public education, but he carried out his constitutional responsibility to enforce the law by implementing desegregation in the District of Columbia. Not all state governments were quick to comply with the Supreme Court’s order to integrate “with all deliberate speed” and many fought against it openly. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus ordered his state’s National Guard to block the entry of nine newly-enrolled African American students to Central High School in Little Rock. A violent mob gathered in front of the school, and city police failed to control it. Finally, when asked for assistance by the Mayor of Little Rock, President Eisenhower believed his constitutional duty to take care that the laws were faithfully executed left him no choice but to intervene, even to the point of using military force against American citizens.

Lesson

LessonGeorge W. Bush and the Supreme Court Case of Bush v. Gore (2000)

The controversy of the election of 2000, unlike the elections of 1800 and 1824, was not at the national level but in a single state. After the United States Supreme Court halted a statewide manual recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court, Florida’s electoral votes—and the Presidency—went to George W. Bush. In this lesson, students will explore the statutes, arguments, and court decisions that led to the Supreme Court’s ruling. Finally, they will evaluate the Court’s decision.

Lesson

LessonGeorge W. Bush and the War on Terror

After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States, George W. Bush demanded that the Taliban government in Afghanistan turn over Osama bin Laden to the US as well as shut down Al-Qaeda training camps in the country. When the Taliban refused, Bush ordered strikes on the country. After hundreds of enemy combatants were captured on the battlefield in Afghanistan, in the US, and around the world, the question of how detainees in the War on Terror should be treated became problematic. Were accused terrorists criminals, or were they illegal combatants (aggressors guilty of breaking laws of war)? Bush’s answer to that question—that they were illegal combatants not entitled to due process protections of US law, but subject to Military Tribunals—became harder and harder to justify to the American people as time wore on.

Lesson

LessonGeorge Washington and Jay’s Treaty

In his every action, President George Washington recognized the significance of the precedents he set. His efforts to implement constitutional provisions in order to steer the United States through an early foreign policy challenge resulted in Jay’s Treaty—a pact vilified in its own time, but ultimately vital in keeping the United States out of a war with Britain.

Lesson

LessonGeorge Washington and the Whiskey Rebellion

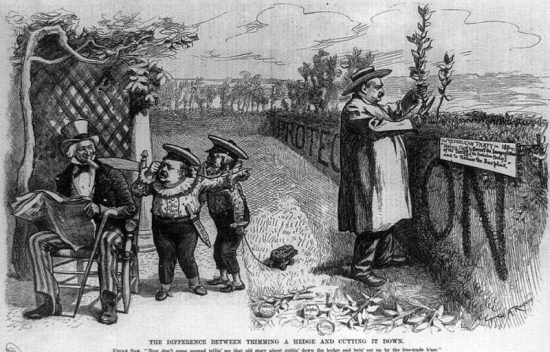

George Washington, always aware that as the new nation’s first President, his every action would be “drawn into precedent,” conducted himself both deliberately and decisively when farmers across the US resisted a new federal excise tax on liquor. He publicly involved other branches and levels of government in his decision process, and issued proclamations calling for peaceful resolutions before using military force to quash what has come to be known as the Whiskey Rebellion. His political opponents charged Washington and his political party with exaggerating (if not manufacturing) the crisis, and called his decision to lead several thousand militia troops against the farmers heavy-handed. However one judges Washington’s action, the events became the first public test of the President’s power to enforce federal law in the new commercial republic.

Lesson

LessonGrover Cleveland and the Texas Seed Bill Veto

Cleveland understood his constitutional legislative responsibility as preventing harmful bills from becoming law, rather than promoting what he saw as beneficial ones. Using the veto, Cleveland stopped the federal government from taking on what he saw as a “paternal” role toward citizens, whether that role came in the form of excessive or fraudulent pension payouts, or in proposed relief for drought-stricken farmers in Texas. These principled stances brought him many enemies, but he did not waver from his commitment to exercising only the powers warranted by the Constitution. One American author said that Cleveland’s “patriotic virtues have won for [him] the homage of half a nation and the enmity of the other half. This places [his] character upon a summit as high as Washington’s.”

Lesson

LessonHerbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the Great Depression

Perhaps no two Presidents in American history had such radically different views about the constitutional powers of the federal government than Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Hoover believed in a limited federal power whose chief purpose was to foster individual liberty and responsibility, while Roosevelt believed that the federal government had broad powers to promote the general welfare. Each President drew upon his views of federal power in his approaches to solving the problems posed by the Great Depression. In this lesson, students will examine the public speeches of each man to better understand their views of the primary purposes and powers of the federal government, a debate which continues today.

Lesson

LessonJames Buchanan and the Dred Scott Decision

During the mid-Nineteenth Century, all three branches of the United States government wrestled with the question of whether the unrestricted spread of slavery was protected by the Constitution. In this lesson, students will evaluate President James Buchanan’s reaction to the Dred Scott decision in light of our nation’s highest principles.

Lesson

LessonJames Madison and the Bonus Bill

James Madison, justly recognized as the "Father of the Constitution," believed that republican liberty was best preserved by the strict enumeration of governmental powers. At the Constitutional Convention, Madison recommended that the national government be empowered to grant charters of incorporation for the construction of canals in order to promote transportation and commerce among the states. This recommendation, however, was not adopted by the delegates. Decades later, President Madison refused to sign legislation authorizing the expenditure of federal funds to support “internal improvements.” With this veto, Madison revealed the depth of his commitment to a strict interpretation of the principle of delegated and enumerated powers.

Lesson

LessonJimmy Carter and the Panama Canal Treaty

President Jimmy Carter’s approach to foreign affairs called for correcting what he saw as injustices, and repudiating American colonialism. Though both negative public opinion and Senate objection originally stood in his way, Carter was able achieve the two-thirds majority necessary for Senate ratification of the Panama Canal Treaties of 1977. His methodical and wide-ranging approach to “advice and consent of the Senate” was a key reason for the smooth transfer of the Panama Canal Zone to Panama.

Lesson

LessonJohn Adams and the Alien and Sedition Acts

John Adams was not a “War President”: he did not lead the country through war as Commander in Chief. However, much of his administration was devoted to avoiding war. The 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts, viewed then by some and now by most as a serious challenge to the First Amendment, were signed into law by Adams, who maintained that “national defense is one of the cardinal duties of a statesman.” He did not ask for the controversial sedition law that limited freedom of speech and press, but believed, as Congress did, that provisions facilitating the deportation of foreign nationals and the discouragement of newspaper dissent would help strengthen the United States in the event of war with France. Adams achieved his goal of keeping the US out of war, but history has condemned his decision to sign and enforce this series of laws.

Lesson

LessonJohn Quincy Adams and the Election of 1824

The Election of 1824 was the first to be decided in the House of Representatives after the Twelfth Amendment was passed. Jackson received the most electoral votes and the greatest percentage of the popular vote (inasmuch as it existed in 1824), but the House voted for John Quincy Adams. In this lesson, students explore the election of 1824 and evaluate the Electoral College system.

Lesson

LessonLyndon Johnson and Ronald Reagan: Two Views of Federal Power

While questions were raised in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries over the proper distribution of power between state and federal governments, debate over the power of the federal government to regulate the every day affairs of the people intensified in the second half of the Twentieth Century. Lyndon Johnson, interpreting Congress’s role to promote the “general welfare” broadly, assembled a team of experts to discover ways to improve society, and sent dozens of bills to Congress which became Great Society programs intended to benefit the poor and the elderly. Ronald Reagan, by contrast, called the War on Poverty a failure, and proposed budgets which reduced spending on social programs while increasing the size and capabilities of the military. Additionally, Reagan called for lower taxes to spur economic growth, reward perseverance and encourage personal responsibility. The two Presidents had markedly different views on the purposes and constitutional powers of the federal government and carried out the duties of their offices accordingly.

Lesson

LessonLyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and the War Powers Resolution

Beginning in 1812 and for the next hundred years, US Presidents asked for and received congressional declarations of war against England, Mexico, Spain, Japan, and European powers. During the Cold War, President Harry Truman sent troops to Korea as part of a UN force without a congressional declaration of war. President John F. Kennedy sent troops to defend South Vietnam. Congress never declared war, but years later passed the Tonkin Resolution authorizing President Lyndon Johnson to use force against North Vietnam. In reaction to US involvement in Vietnam, Congress passed the War Powers Act which limited the President’s authority to commit American troops abroad without Congress’s approval. The law was passed over the veto of President Richard Nixon, who argued the law was an abridgement of the President’s authority as Commander in Chief. The Act raises the questions: How far does the President’s power as Commander in Chief extend? And, how much of that power can be limited by Congress?

Lesson

LessonRichard Nixon and the Watergate Scandal

In 1974, Richard M. Nixon became the only President in US history to resign from the presidency. After administration operatives were caught breaking into the Democratic Party headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, DC, Nixon covered up the crime. A Congressional investigation produced a stunning revelation: The Oval Office had a recording system that taped all the President’s conversations. The tapes could prove whether Nixon himself had ordered the cover-up. The Supreme Court rejected Nixon’s claim that executive privilege allowed him to withhold the tapes. With members of his own Republican Party turning against him and the House drawing up impeachment charges that were sure to pass, Nixon resigned the presidency on August 9. The events raised serious questions about the definition, use, and abuse of executive authority.

Lesson

LessonRutherford B. Hayes and the Disputed Election of 1876

The US Constitution provides an orderly process for electing the President, as described in Article II and the Twelfth Amendment. However, in the election of 1876, two conflicting sets of electoral votes were submitted by each of four states. The Constitution provided no process for determining the legitimate set of votes. Acting outside any constitutional mandate, Congress created a special commission to investigate the returns from Oregon, South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. Voting along party lines, the commission ruled that Rutherford B. Hayes had won the disputed election.

Lesson

LessonThe Election of 1800

The 1800 election was a major test of whether the young republic and its Constitution would live beyond its Founding generation. It was the first election in which two competing political parties engaged in an extended campaign against one another to win the presidency. This challenge was made more difficult by the fact that the new Constitution’s system for electing a President was not designed with political parties in mind. In fact, the Constitution’s process for electing the President had been designed to limit the influence of political parties. In the election of 1796, this method of electing the President led to the potentially dangerous situation of joining a President with a Vice President from the opposing party. In the election of 1800, this method of electing the President led to a tie, which was only settled after a long battle in the House of Representatives. The republic endured the election of 1800, but it was clear to most that the constitutional process for electing the President needed to be amended. To do so, Congress passed the Twelfth Amendment in 1803; the states ratified the amendment in 1804.

Lesson

LessonThe Election of 1860

The election of 1860 was the only election in our history that did not result in a peaceful transfer of power. As political developments changed the way the Constitution’s compromises on slavery were understood and applied, Americans from both North and South expressed fears about conspiracies to either impose or prohibit slavery throughout the nation. Fearing a loss of power within the Union, many Southerners revisited arguments about the nature of the Constitution. Some argued that the Constitution was a compact among the states, and that interpretation seemed to allow for states to secede, or withdraw from that compact. After the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, was elected President in 1860—without even appearing on the ballot in ten Southern states—Southern states rapidly took action to secede from the Union, and President Lincoln took action to keep the Union together.

Lesson

LessonThe Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

When Andrew Johnson became President upon Lincoln’s assassination, he hoped to restore the Union according to a plan that would be lenient toward the South. Lacking congressional support and political skills, Johnson found himself in a show-down with Republicans in Congress who wanted to remake the South in the image of the North, raise up blacks and poor whites, and guarantee full civil and political rights for the freedmen. This clash of goals and strategies led to the first presidential impeachment trial in our history—a test of the constitutional principles of separation of powers and checks and balances. In the end, the Founders’ mechanism of three co-equal branches of government proved strong enough to resolve the crisis.

Lesson

LessonThe Impeachment of Bill Clinton

In the highly charged partisan politics of the 1990s, President Bill Clinton’s personal indiscretions led to the second impeachment trial in our history. Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr was investigating Clinton’s pre-presidential financial dealings. In a separate case, Clinton was being sued by Paula Jones for sexual harassment. Jones called a young White House intern named Monica Lewinsky who had been having an relationship with the President to give testimony. Clinton denied the Lewinsky affair under oath in his deposition in the Jones case. This denial caught Starr’s attention, who suspected the President had committed perjury and obstructed justice. Starr assembled a grand jury and issued dozen of subpoenas, and eventually offered Lewinsky immunity in return for her testimony. When Clinton testified for Starr’s grand jury, he gave evasive answers. He ultimately admitted the Lewinsky affair to the American people that night. The House of Representatives impeached Clinton in 1998 on strict party lines, but in the Senate trial, Republicans fell far short of the two-thirds majority needed to convict.

Lesson

LessonThe Resignation of Richard Nixon

Shortly before Richard Nixon was re-elected President in 1972, individuals connected with his re-election campaign were arrested while breaking into Democratic Party Headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington DC. Nixon was re- elected by an overwhelming margin, but questions surrounding his knowledge of the break-in, and his attempt to cover it up would not go away. During these investigations, Nixon’s Vice President, Spiro Agnew, was forced to resign on unrelated corruption charges. According to the Twenty-Fifth Amendment, the President must nominate a new Vice President when that office becomes vacant, and both houses of Congress must approve that Vice President. Because few in Congress believed that Nixon’s presidency would survive, key members of Congress told Nixon to nominate as Vice President a distinguished Republican Member of Congress, Gerald Ford. After Nixon’s resignation, Ford was sworn in as President and made the extremely unpopular decision of issuing Nixon a full pardon “for all offences against the United States.”

Lesson

LessonTheodore Roosevelt and the Bully Pulpit

While many of President Theodore Roosevelt’s predecessors saw themselves as servants of Congress, Roosevelt saw the President as the servant or agent of the people. He transformed the legislative role of the President from nominal legislative advisor to outspoken advocate of policies that he thought would strengthen America. Where the Founders believed that powers not granted were forbidden, Roosevelt asserted that powers not forbidden were granted. He was aware that he was shaping the Presidency in a way his detractors would criticize. In his autobiography, Roosevelt wrote that he did not “usurp” power, but that he did “greatly broaden” executive authority. One way he did this was to use his position as a “bully pulpit.”

Lesson

LessonThomas Jefferson and the Louisiana Purchase

President Thomas Jefferson, elected at the end of the Quasi-War with France, faced domestic unease when Spain returned Louisiana to France at Napoleon’s insistence. Aware of the strategic importance of New Orleans and wary of Napoleon’s desire to build an empire in North America, Jefferson sent negotiators to France to purchase land east of the Mississippi. As time went on, though, France had other priorities and in the spring of 1803 offered the United States the whole Louisiana territory—more than 800,000 acres—for $15 million. Jefferson had always feared the costs of loose construction of the powers delegated to the national government in the Constitution, and the Constitution did not provide for the incorporation of news lands into the US. Jefferson urged bringing the issue to the people to approve with a constitutional amendment, but a special session of Congress disregarded his draft amendment. The Senate ratified the Louisiana Purchase Treaty in October of 1803. While Jefferson did his best to follow what he believed was proper constitutional procedure, not enough of his contemporaries agreed with him and he eventually assented.

Lesson

LessonWar in the Early Republic

The War of 1812 was the United States of America’s first declared war, but it was far from being the nation’s first foreign conflict. Presidents George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison all countenanced various adversaries and all took different approaches to exercising the powers vested in the President under the Constitution. Washington, concerned with avoiding foreign entanglements, declared the US would stay neutral when France and England went to war, and set off a firestorm of criticism for doing so. Adams also succeeded in avoiding war after attempting to engage France diplomatically and pursuing domestic policies designed to quiet support for the French. Jefferson, frustrated with his two predecessors for having continued the traditional practice of paying off the Barbary pirates, declared an end to the bribes and sent a naval force to deal with the pirates. Madison sought and received the first-ever congressional declaration of war (against Britain), and also declared victory against the Barbary pirates after a second skirmish in 1815.

Lesson

LessonWoodrow Wilson and the Espionage Act

President Woodrow Wilson worried about the influence of subversive elements in the United States—including at first German-Americans and Irish-Americans, and later socialists, communists, and anarchists. In 1915, Wilson asked Congress to pass laws designed to “crush out” the “creatures of passion” who he believed might topple the US government. Congress heeded this call with the Espionage Act of 1917, amended by the Sedition Act in 1918. Criticized by some as unconstitutional, these laws were defended by Wilson and Congress as war measures to enhance the security of the United States.

Lesson

LessonWoodrow Wilson and the Treaty of Versailles

As President Woodrow Wilson negotiated with foreign leaders to write the Treaty of Versailles, he was forced to make extreme concessions from his peace plan, the Fourteen Points. He remained confident in the League of Nations—one of his Fourteen Points—to ameliorate remaining injustices in the Treaty. When he sought the Senate’s consent to the treaty, he found some members of that body so opposed to joining the League of Nations that the Treaty was rejected by votes on three occasions. Wilson neither sought nor accepted the Senate’s advice on the Treaty, and for the first time in American history, the Senate refused to ratify a peace treaty negotiated by the President.