Documents to Examine (A-M) – Lawrence v. Texas (2003)

DOCUMENT A

Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book IV, 1765-1769

IV. WHAT has been here observed … ought to be the more clear in proportion asthe crime is the more detestable, may be applied to another offence, of a still deeper malignity; the infamous crime against nature, committed either with man or beast.…

I WILL not … dwell any longer upon a subject, the very mention of which is a disgrace to human nature. …Which leads me to add a word concerning its punishment.

THIS the voice of nature and of reason, and the express law of God, determine to be capital. Of which we have a signal instance, long before the Jewish dispensation, by the destruction of two cities by fire from heaven: so that this is an universal, not merely a provincial, precept.

- How did English common law view and punish sodomy?

DOCUMENT B

Federalist No. 51, 1788

It is of great importance in a republic not only to guard the society against the oppression of its rulers, but to guard one part of the society against the injustice of the other part. Different interests necessarily exist in different classes of citizens. If a majority be united by a common interest, the rights of the minority will be insecure.…

In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice and the general good.

- According to this document, what two possible sources of injustice exist?

- According to this document, why does the extended nature of the American republic help ensure justice?

DOCUMENT C

Concurring Opinion, Railway Express Agency v. New York, 1949

The framers of the Constitution knew, and we should not forget today, that there is no more effective practical guaranty against arbitrary and unreasonable government than to require that the principles of law which officials would impose upon a minority must be imposed generally. Conversely, nothing opens the door to arbitrary action so effectively as to allow those officials to pick and choose only a few to whom they will apply legislation and thus to escape the political retribution that might be visited upon them if larger numbers were affected. Courts can take no better measure to assure that laws will be just than to require that laws be equal in operation.

- Restate this assertion in your own words

DOCUMENT D

Majority Opinion, Griswold v. Connecticut, 1965

The present case … concerns a relationship lying within the zone of privacy created by several fundamental constitutional guarantees.…

We deal with a right of privacy older than the Bill of Rights—older than our political parties, older than our school system. Marriage is a coming together for better or for worse, hopefully enduring, and intimate to the degree of being sacred. It is an association that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects. Yet it is an association for as noble a purpose as any involved in our prior decisions.

- What right to privacy was defined in Griswold v. Connecticut?

- What is the “noble purpose” that this privacy promotes?

DOCUMENT E

Majority Opinion, Eisenstadt v. Baird, 1972

The marital couple is not an independent entity with a mind and heart of its own, but an association of two individuals each with a separate intellectual and emotional makeup. If the right of privacy means anything, it is the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted governmental intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child … the State could not, consistently with the Equal Protection Clause, outlaw distribution [of birth control] to unmarried but not to married persons.…

- What is the difference between this decision and the one in the Griswold case (Document D)?

DOCUMENT F

Majority Opinion, Roe v. Wade, 1973

The Constitution does not explicitly mention any right of privacy. In a line of decisions, however, … the Court has recognized that a right of personal privacy, or a guarantee of certain areas or zones of privacy, does exist under the Constitution. This right of privacy… is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.

- How did the decision in Roe build on the decisions in Griswold (Document D) and Eisenstadt (Document E) with respect to the right of privacy?

DOCUMENT G

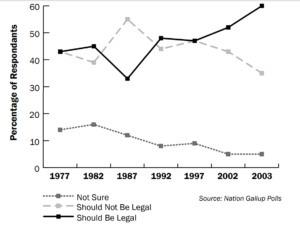

Gallup Poll: “Americans’ Views on Homosexuality and the Law,” 1977-2003

Question: “Do you think homosexual relations between consenting adults should or should not be legal?”

- What trends do you see concerning Americans’ support for legalizing homosexual activity?

DOCUMENT H

Majority Opinion, Bowers v. Hardwick, 1986

We think it evident that none of the rights announced in [Griswold and Eisenstadt] bears any resemblance to the claimed constitutional right of homosexuals to engage in acts of sodomy. …Moreover, any claim that these cases [mean] that any kind of private sexual conduct between consenting adults is constitutionally insulated from state proscription is unsupportable.

Plainly enough, otherwise illegal conduct is not always immunized whenever it occurs in the home. Victimless crimes, such as the possession and use of illegal drugs, do not escape the law where they are committed at home.…

[R]espondent asserts that there must be a rational basis for the law, and that there is none in this case other than the presumed belief of a majority of the electorate in Georgia that homosexual sodomy is immoral and unacceptable. This is said to be an inadequate rationale to support the law. The law, however, is constantly based on notions of morality, and if all laws representing essentially moral choices are to be invalidated under the Due Process Clause, the courts will be very busy indeed.…

- How does the Court contrast the right to privacy protected in the Griswold and Eisenstadt cases with the right claimed in Bowers?

- What statement does the Court make about morality and the law?

DOCUMENT I

Majority Opinion (6-3), Lawrence v. Texas, 2003

Liberty protects the person from unwarranted government intrusions into a dwelling or other private places. …Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct. …The laws involved in Bowers [Document H] and here … purport to do no more than prohibit a particular sexual act. Their penalties and purposes, though, have more far-reaching consequences, touching upon the most private human conduct, sexual behavior, and in the most private of places, the home. …It suffices for us to acknowledge that adults may choose to enter upon this relationship in the confines of their homes and their own private lives and still retain their dignity as free persons. …The liberty protected by the Constitution allows homosexual persons the right to make this choice.

It must be acknowledged, of course, that the Court in Bowers was making the broader point that for centuries there have been powerful voices to condemn homosexual conduct as immoral. The condemnation has been shaped by religious beliefs, conceptions of right and acceptable behavior, and respect for the traditional family. For many persons these are not trivial concerns but profound and deep convictions accepted as ethical and moral principles to which they aspire and which thus determine the course of their lives. These considerations do not answer the question before us, however. The issue is whether the majority may use the power of the State to enforce these views on the whole society through operation of the criminal law. Our obligation is to define the liberty of all, not to mandate our own moral code.…

Had those who drew and ratified the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment known the components of liberty in its manifold possibilities, they might have been more specific. They did not presume to have this insight. They knew times can blind us to certain truths and later generations can see that laws once thought necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress. As the Constitution endures, persons in every generation can invoke its principles in their own search for greater freedom.

- Restate the majority opinion in two to three sentences.

DOCUMENT J

Concurring Opinion, Lawrence v. Texas, 2003

I agree with the Court that Texas’ statute banning same-sex sodomy is unconstitutional. …I base my conclusion on the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause. …The statute at issue here makes sodomy a crime only if a person “engages in deviate sexual intercourse with another individual of the same sex.” Sodomy between opposite-sex partners, however, is not a crime in Texas. That is, Texas treats the same conduct differently based solely on the participants.

- Why does the concurring Justice believe the Texas law is unconstitutional?

DOCUMENT K

Dissenting Opinion (Antonin Scalia), Lawrence v. Texas, 2003

[The Texas sodomy law] undoubtedly imposes constraints on liberty- so do laws prohibiting prostitution, recreational use of heroin, and, for that matter, working more than 60 hours per week in a bakery. But there is no right to “liberty” under the Due Process Clause, though today’s opinion repeatedly makes that claim… The Fourteenth Amendment expressly allows States to deprive their citizens of liberty so long as “due process of law” is provided.…

[T]he Due Process Clause prohibits States from infringing fundamental liberty interests, unless the infringement is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest. [emphasis original]

- What argument does Justice Scalia make about the Due Process Clause in his dissent?

DOCUMENT L

Dissenting Opinion (Clarence Thomas), Lawrence v. Texas, 2003

The law before the Court today “is … uncommonly silly.”…If I were a member of the Texas Legislature, I would vote to repeal it. Punishing someone for expressing his sexual preference through noncommercial consensual conduct with another adult does not appear to be a worthy way to expend valuable law enforcement resources.

Notwithstanding this, I recognize that as a member of this Court I am not empowered to help petitioners and others similarly situated. My duty, rather, is to “decide cases ‘agreeably to the Constitution and laws of the United States.’ ” And, just like Justice Stewart [dissenting in Griswold v. Connecticut, 1965], I “can find [neither in the Bill of Rights nor any other part of the Constitution a] general right of privacy.”…

- If Justice Thomas believes the law is “uncommonly silly,” why does he not find it unconstitutional?

DOCUMENT M

“What Are You Doing Here?” 2003

DIRECTIONS: Answer the Key Question in a well-organized essay that incorporates your interpretations of Documents A-M, as well as your own knowledge of history.

KEY QUESTION: Analyze how the Court’s definition of privacy evolved from 1965 to 2003.