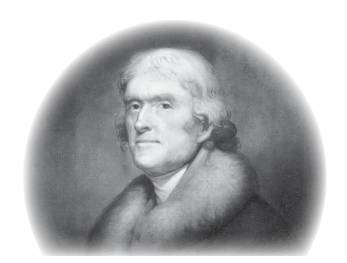

Humility: Thomas Jefferson and the Rewards of Humility Essay

A traveler, after stopping for the night at a Virginia inn, struck up a conversation with “a plainly-dressed and unassuming” stranger. The stranger “introduced one subject after another into the conversation” and demonstrated himself to be “perfectly acquainted with each.” When the topic was the law, the traveler assumed he was speaking with a lawyer. But when the discussion moved to medicine, the traveler surmised that the stranger must be a physician. When their talk turned to theology, the traveler determined that the man must be a clergyman. “Filled with wonder” that one person could be so well informed about so many things, after the conclusion of the conversation the traveler sought out the proprietor of the establishment. “Oh,” said the innkeeper, “I thought you knew the Squire.” What the innkeeper said next “astonished” the traveler. The stranger, “whom he had found so affable and simple in his manners,” was the third president of the United States.

Shy by nature, Thomas Jefferson rarely bragged or called attention to himself. His rambling, stammering, tongue-tied expression of affection for a young woman who caught his eye during his student days at the College of William and Mary failed to capture her interest—and soon she married someone else. Even as a revolutionary, Jefferson stood out as a result of his reticence. As John Adams remembered, “during the whole time I sat with him” in the Continental Congress, “I never heard him utter three sentences together.” Even when delivering his First Inaugural Address, Jefferson’s voice was so soft that few could actually hear it.

But Jefferson’s natural reserve often seemed to work to his advantage. Then, as now, shyness rarely characterized public officeholders. Yet then, in the eyes of many, an inclination toward humility could actually merit a good deal of trust. The generation that came of age during the American Revolution felt weary of government and its monopoly on the lawful use of force. From Caesar to Cromwell,leaders throughout history had abused their power—even when claiming to act in behalf of the people. Many accepted that the more power the government possessed, the less power people possessed, as individuals, to govern themselves. What could be more admirable than a government official who appeared to possess neither an inflated view of himself nor much inclination to exercise power or enjoy its trappings?

While people criticized his predecessors for embracing ceremonies and symbols characteristic of European monarchy, Jefferson rejected what he called “the rags of royalty” and instead served as a role model for more humble, less grandiose gestures reflecting “republican simplicity.” While Washington and Adams rode to their inaugurations in liveried coaches, Jefferson walked. Instead of elaborate state dinners featuring seating arrangements reflecting guests’ supposed importance, Jefferson favored smaller dinners and allowed visitors to select their own seats at round tables. People calling on President Jefferson expressed surprise when the man who opened the executive mansion’s front door was not a servant but instead the president himself. Anthony Merry, the British ambassador, even felt insulted when Jefferson greeted him while wearing slippers on his feet.

Jefferson’s modest attire and simple manners drew praise as well as criticism, however, reinforcing his image as the “Friend of the People.” They also help to make sense of the many stories in which people interact with him fully unaware of his identity. When, early on summer mornings, Jefferson walked to the Washington Navy Yard and struck up conversations with dockworkers and shipwrights, many had no idea that before them stood the President. A similar thing happened when President Jefferson, out riding on horseback with a small group of gentlemen, encountered a man on foot who needed help crossing a stream. Jefferson reached down, pulled the man up to share his saddle, and rode with him to the other side. Afterwards, as Jefferson continued on, a member of his party asked the man why, of all those on horseback, he had not requested assistance from one of the others.“From their looks, I did not like to ask them,” he replied. “The old gentleman looked as if he would do it, and I asked him.” The man, of course, was surprised to then learn that “the old gentleman” was Thomas Jefferson.

It may well be true that Jefferson had little to gain from bragging or putting on airs. In this era before photography and television, his face was not famous, but nearly all knew his name and acknowledged his many accomplishments. His shyness, humility, and habitual self-effacement served mainly to add luster to his character—a fact he could not have failed to recognize. Consider the epitaph that he asked be inscribed on his tombstone: “Here was buried Thomas Jefferson, Author of the Declaration of American Independence, of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom, and Father of the University of Virginia.” Who could have missed the fact that Jefferson chose not to mention his service as legislator, governor, secretary of state, vice president, and president? Who cannot admire that Jefferson most wished to be remembered not for the instances in which people gave power to him, but instead for the acts by which he gave power to the people?

– Robert M. S. McDonald

United States Military Academy