Alexander Hamilton and the National Bank

Written by: Jack Rakove, Stanford University

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain how and why political ideas, institutions, and party systems developed and changed in the new republic

Suggested Sequencing

This Narrative should be assigned to students at the beginning of their study of Chapter 4 and can be used in conjunction with the Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton, Writings on the National Bank, 1785-1792Primary Source, The National Bank Debate Lesson, and the “Strict” or “Loose”: Was the National Bank Constitutional? Point-Counterpoint.

As one of General Washington’s aides-de-camp during the Revolutionary War, Alexander Hamilton spent many of his leisure hours reading about commerce and banking. The amount of knowledge he gained impressed those who knew him. In the summer of 1780, when the Continental Congress was trying desperately to keep its army in the field, the New York delegate James Duane asked Hamilton to analyze “the defects of our present system.” Hamilton replied with a lengthy letter assessing the various errors Congress had made and proposing the remedies he thought necessary. Perhaps, Hamilton noted, his proposals should be viewed more as “the reveries of a projector rather than the sober views of a politician.” In fact, his lengthy letter of September 3, 1780, anticipated many of the successful policies Hamilton later pursued as President Washington’s first secretary of the treasury.

High on Hamilton’s list of proposals in 1780 was the creation of a national bank. The inspiration for this idea came from Great Britain. One critical element in the development of British imperial power in the eighteenth century had been the creation of a national bank in 1694. “The Bank of England unites public authority and faith with private credit,” Hamilton wrote Duane, “and hence we see what a vast fabric of paper credit is raised on a visionary basis.” Why could Americans not try the same “experiment”?

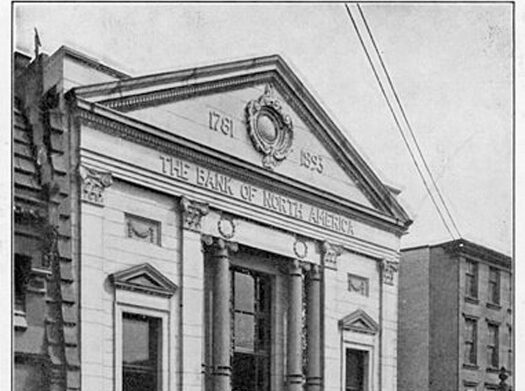

In fact, the Continental Congress did establish the Bank of North America in Philadelphia in 1781. Yet because Congress lacked the authority to tax, it could not make enough deposits in the bank to adequately support it. Other banks were founded in Boston, New York, and Baltimore later in the decade, but few Americans really understood how banks actually worked. Many skeptics worried about the financial power banks could wield.

The Bank of North America was founded by the Continental Congress in Philadelphia and failed due to Congress’s lack of ability to tax.

The adoption of the Constitution in 1787 altered this situation in fundamental ways. The new Congress could collect its own taxes, notably through duties levied on foreign imports, and then deposit these revenues in a national bank. In his famous Report on a National Bank, presented to the House of Representatives in mid-December 1790, Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton explained in great detail how his proposed system would operate. Congress would grant a twenty-year charter of incorporation to a Bank of the United States, which would be funded by an initial deposit of $10 million, an immense value for that time. The U.S. government would purchase one-fifth of the bank’s stock; the rest of the initial deposit would come from the sale of shares in the bank to private investors. The government would deposit its tax revenues in the Bank of the United States, and the bank, in turn, would loan its money to the government and to private businesses to stimulate their productivity and growth.

As a public policy, the founding of a national bank was a brilliant stroke. Hamilton’s Report on a National Bank was a tribute to the depth of his thinking and the bitter lessons he and other officers in the Continental Army had drawn from the Revolutionary War, when neither the Continental Congress nor the state governments had proved capable of keeping their soldiers adequately paid and supplied. The success of the eighteenth-century British Empire was the model that knowledgeable observers wanted to apply, and Hamilton understood its lessons well.

There was, however, one great obstacle to the completion of Hamilton’s plan. The creation of a national bank required an act of incorporation from Congress. Its critics, led by Virginia congressman James Madison, could legitimately object that Congress had no constitutional power to issue charters of incorporation. Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution enumerated the legislative powers that Congress possessed. The power to issue charters of incorporation – a power that could be used to facilitate the building of bridges, turnpikes, or canals, or to create banks – was conspicuously absent from this critical section of the Constitution.

Most members of Congress knew that Madison had kept detailed notes of the debates at the Philadelphia convention. He told his colleagues in the House that a motion to grant Congress the power to issue charters of incorporation had been offered at the Convention and rejected. In fact, Madison had been its author. Members of Congress respected Madison’s work in framing the Constitution. But other representatives who had also attended the Convention replied that Madison’s notes and recollections did not necessarily capture the general sense of the framers of the Constitution. They could have rejected his motion simply because it was superfluous, not because they wanted to deny Congress the power of incorporation.

That was also the constitutional logic behind Hamilton’s proposal. In his view, which a majority of members of both houses of Congress shared, the critical text of the Constitution was the necessary and proper clause in Article I, Section 8, which stated Congress could make laws related to the other enumerated powers even if not listed. Even before the bank bill was proposed, Congress had relied on the authority of this clause in enacting numerous other laws. To Hamilton’s way of thinking, the necessary and proper clause gave Congress enormous discretion in deciding how its other assigned powers would be implemented. There was no question that a national bank modeled on the British example would be a useful means to accomplish the basic ends of government.

An 1806 portrait of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull. One of the republic’s most brilliant statesmen, Hamilton worked with Congress to create the new nation’s financial system.

Madison pursued a different line of reasoning in the House of Representatives. He still believed the legislature was the one branch of government most likely to overextend its legitimate constitutional authority. If Congress could use the necessary and proper clause to extend its jurisdiction, there would be no effective limit on its authority. Madison also believed that the power to create corporations had to be explicitly authorized and was not something that could be created by “implication” from the text of the Constitution.

These reservations did not persuade Congress. After the bank bill was passed, President Washington had to review the constitutional issues before deciding whether to sign or veto it. Within the cabinet, Madison’s close friend, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, renewed the arguments against a national bank. In his view, the word “necessary” in the necessary and proper clause meant something more than convenient or very useful. Its true meaning in this case, Jefferson thought, was closer to indispensable. If Congress had other ways to secure its objectives, a nationally incorporated bank was unnecessary and improper. He also thought that a national bank was unconstitutional because the Tenth Amendment reserved all unenumerated powers to the states.

President Washington sided with Hamilton. He deeply respected the opinions of Madison and Jefferson, as well as the additional memorandum provided by Attorney General Edmund Randolph. But Washington allowed Hamilton to have the final word on the matter. Once again, Hamilton produced one of his brilliant comprehensive papers, patiently dissecting and criticizing the arguments made by the three Virginians. In Hamilton’s view, the Constitution vested the national government with “implied, as well as express powers.” Without that reading of the text, the very ends for which the Constitution had been written would often prove unattainable.

Washington knew what those ends were. He and Hamilton shared a common vision of vigorous national power. To secure that end, the Constitution had to be read liberally, not narrowly. The president signed the bill, and the Bank of the United States soon began its very successful operations. But the issue of its constitutionality and the reach of the necessary and proper clause continued to be a source of contention in U.S. politics for nearly half a century.

Review Questions

1. When Alexander Hamilton proposed the national bank, he was

- a large plantation owner

- secretary of state

- secretary of war

- secretary of the treasury

2. Which of the following is true?

- The national bank created under the Articles of Confederation could not issue bank notes.

- Under the Constitution, the government could collect tax revenue .

- The national bank created under the Articles of Confederation could not encourage private investment.

- Under the Constitution, the national bank was prohibited from investing money in private business ventures.

3. Congress was able to charter a national bank by virtue of

- the necessary and proper clause of the Constitution

- the authority given to the judicial branch

- a loose interpretation of the Constitution that called for a regulatory body over the U.S. economy

- the authority given to the executive branch

4. The creation of the Bank of the United States established that

- most governing authority lay with Congress

- new federal entities, such as a national bank, required the approval of all three government branches

- the Constitution could be loosely or broadly interpreted

- the Constitution needed amending

5. All the following were reasons presented in favor of the Bank of the United States except

- the Continental Congress had been unable to pay soldiers during the Revolution

- the Bank would be a depository for government tax revenue

- the Bank was absolutely required for the United States to be able to conduct its business

- the Bank would provide a source of funding for the U.S. government to purchase vast amounts of territory from foreign powers

6. In regards to the national bank, James Madison feared

- the precedent established by its creation could give too much authority to the Executive Branch

- the necessary and proper clause could give Congress the authority to violate individual civil liberties

- the Legislative Branch might overextend its constitutional authority

- the government could create more corporations on a whim

7. A major reason President Washington favored the establishment of a national bank based on Alexander Hamilton’s plan was

- the success of the Bank of England

- the need for investment in U.S. industry

- the problems created by the lack of funding for the troops during the American Revolution

- the national debt created by the French and Indian War

Free Response Questions

- Compare the main points of the arguments for and against the establishment of the Bank of the United States.

- Explain Alexander Hamilton’s reasoning for the necessity of the Bank of the United States.

AP Practice Questions

“The foundation of the Constitution is laid on this ground: – That all powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited to it by the States, are reserved for the States, or to the people.’ Whence it is meant to be inferred, that Congress can in no case exercise any power not Included in those not enumerated in the Constitution. And it is affirmed, that the power of erecting a corporation is not included in any of the enumerated powers. The main proposition here laid down, in its true signification is not to be questioned . . . that all government is a delegation of power. But how much is delegated in each case, is a question of fact, to be made out by fair reasoning and construction, upon the particular provisions of the Constitution, taking as guides the general principles and general ends of governments. It is not denied that there are implied well as express powers, and that the former are as effectually delegated as the [latter].”

Alexander Hamilton, Hamilton’s Opinion as to the Constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, 1791

Refer to the excerpt provided.1. The argument made in the excerpt supports the contention that

- the creation of a national bank must have the consent of the governed

- the Constitution must be interpreted broadly for the government to function properly

- the government cannot create entities such as a national bank because those powers are not implied by the Constitution

- the delegated powers in the Constitution are more significant than the implied powers

2. By the mid- nineteenth century, all the following had had their constitutionality called into question except

- the tariff issue in the 1790s

- the ability of the government to regulate slavery

- the purchase of territory from a foreign government

- the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798

Primary Sources

Hamilton, Alexander. “Opinion on the Constitution of an Act to Establish a Bank” February 23, 1791. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=opinion%20national%20bank%20Author%3A%22Hamilton%2C%20Alexander%22&s=1511311111&r=16

Jefferson, Thomas. “Opinion on the Constitutionality of the Bill for Establishing a National Bank.” February 15, 1791. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=opinion%20national%20bank%20Author%3A%22Jefferson%2C%20Thomas%22&s=1511311111&r=6

Madison, James. “The Bank Bill.” February 8, 1791. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=opinion%20national%20bank%20Author%3A%22Madison%2C%20James%22&s=1511311111&r=9

Suggested Resources

Knott, Stephen, and Tony Williams. Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance That Forged America. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2015.

Leibiger, Stuart. Founding Friendship: George Washington, James Madison, and the Creation of the American Republic. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999.

McCraw, Thomas K. The Founders and Finance: How Hamilton, Gallatin, and Other Immigrants Forged a New Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012.

McDonald, Forrest. Alexander Hamilton: A Biography. New York: Norton, 1979.

Rakove, Jack. Revolutionaries: A New History of the Invention of America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2010.