Andrew Carnegie and the Creation of U.S. Steel

Written by: John Steele Gordon, Independent Historian

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the effects of technological advances in the development of the United States over time

- Explain the socioeconomic continuities and changes associated with the growth of industrial capitalism from 1865 to 1898

- Explain the causes of increased economic opportunity and its effects on society

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with the Were the Titans of the Gilded Age “Robber Barons” or “Entrepreneurial Industrialists”? Point-Counterpoint and the Debating Industrial Progress: Andrew Carnegie vs. Henry George Lesson to highlight the impact businessmen like Carnegie had on industry and philanthropy in the Gilded Age.

Early in 1901, J. P. Morgan, the country’s most powerful banker, merged Andrew Carnegie’s Carnegie Steel Corporation with nine other steel companies to form the world’s largest corporation. The United States Steel Corporation, usually known as U.S. Steel or simply Big Steel, was capitalized at $1.4 billion. To get a sense of how big a sum that was at the turn of the twentieth century, consider that the federal government that year spent only $517 million. The creation of U.S. Steel was the culmination of an era of American industrial consolidation that made many fear such corporations were becoming too powerful, financially and politically, and thereby threatened American democracy.

Morgan and Carnegie could hardly have come from more different backgrounds. Morgan had been born rich in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1837, the son of international banker J. S. Morgan and the grandson of the founder of Aetna Insurance Company. He was well educated, having attended the English High School in Boston and then University of Göttingen in Germany. He was fluent in French and German. By the 1870s, Morgan was a partner in the Wall Street firm of Drexel, Morgan and Company and acted as the New York agent for his father’s bank, which was headquartered in London. On his father’s death, he formed J. P. Morgan and Company.

Andrew Carnegie had been born in 1835 in a one-room house in Dunfermline, Scotland, the son of a handloom weaver. But when the weaving of cloth was mechanized in the 1840s, the Carnegies became impoverished. Under the leadership of Carnegie’s strong-willed mother, the family emigrated to Allegheny, Pennsylvania, in 1848, when Andrew was 13 years old. With his formal education, such as it was, at an end, he found work as a bobbin boy in a cotton mill, earning $1.20 for laboring 12 hours a day, six days a week.

Andrew Carnegie, pictured here in his later years, lived a true rags-to-riches story by transforming himself from a poor Scottish immigrant into one of the country’s wealthiest men.

Andrew Carnegie, pictured here in his later years, lived a true rags-to-riches story by transforming himself from a poor Scottish immigrant into one of the country’s wealthiest men.In 1849, Carnegie went to work at the Ohio Telegraph Company, earning $2.00 a week as a messenger boy. He soon mastered telegraphy, learning to “read” messages by ear, and was promoted to operator. There he met Colonel James Anderson, who let working boys borrow books from his personal library, a privilege Carnegie used to the full. He resolved that if he ever became rich, he would give other working boys the same opportunity.

A tireless worker, Carnegie came to the attention of Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad, who hired him as his personal telegrapher at $4.00 a week. By 1859, when he was 24 years old, Carnegie was put in charge of the Western Division of the railroad and was earning $1,500 a year, a middle-class income. Mentored by Scott, who helped him start investing, often in insider deals, Carnegie was a rich man by the end of the Civil War. He invested in iron works and saw potential in the future of steel.

Carnegie was right. Before the 1850s, steel could be made only in small batches and was so expensive that it was limited to specialized applications like sword blades and precision tools, despite being much more versatile and stronger than wrought iron. Then in 1857, the English engineer Henry Bessemer developed a way to make steel in large quantities at a fraction of the old price. Steel quickly began to replace wrought iron in such things as railroad rails and structural beams.

In 1860, the United States had produced only 13,000 tons of steel. In 1880, it produced 1,467,000 tons. Twenty years later, it produced 11,227,000 tons, more than England and Germany combined. By that time, steel was the measure of a country’s industrial might, and Carnegie was primarily responsible for American strength in steel production. He left the employ of the Pennsylvania Railroad to devote himself full time to overseeing the production of iron and steel. But he was careful to maintain close relationships with Thomas Scott and J. Edgar Thomson, the railroad’s president, and the railroad was soon his best customer. When Carnegie built his first steel mill, he named it after Thomson.

Carnegie’s business philosophy was simple. He retained a large part of the profits earned in good times to tide him over and give him flexibility in bad times. He used those earnings to expand during depressions, when construction costs were low and competitors were forced to the wall and had to sell cheaply. Most importantly, he was open to constant technological and business innovation to reduce operating costs even by a little, because they had much more impact on profits than construction costs. The strategy was a great success. In addition, Carnegie Steel bought up its sources of raw materials and shipping (in a strategy called vertical integration) and bought out and absorbed its competitors (horizontal integration) to dominate the steel industry. By the 1890s, it was the largest and most profitable steel company in the world.

But Carnegie felt a keen sense of social responsibility, as recounted in an article he wrote called “The Gospel of Wealth.” In it he argued that “the man who dies rich dies disgraced.” As he approached his sixties, he wanted to spend less time making money and more time giving it away by dedicating himself to philanthropy.

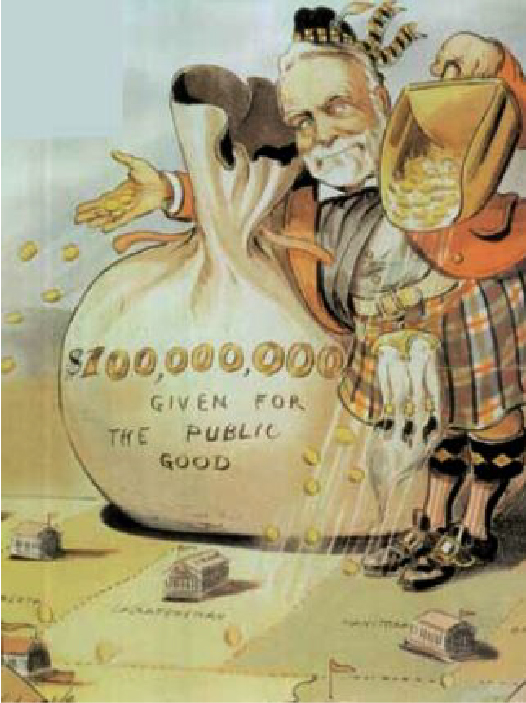

Andrew Carnegie, depicted in this 1903 cartoon, believed that he and his fellow wealthy industrialists should use their surplus wealth to better society, rather than bequeathing it to their heirs.

Andrew Carnegie, depicted in this 1903 cartoon, believed that he and his fellow wealthy industrialists should use their surplus wealth to better society, rather than bequeathing it to their heirs.The president of Carnegie Steel was Charles Schwab. In late 1900, a dinner in his honor was given in New York City and attended by many of the country’s industrial and financial elite, including Morgan, who sat next to Schwab. A gifted public speaker, Schwab stood up after the dinner and extolled the strength and efficiency of the American steel industry. But, he argued, it could grow even larger and more powerful compared with its European rivals. A single company with the most efficient mills in the country could control the industry through economies of scale, advanced technology, and specialization. The resulting conglomerate, Schwab declared, would dominate the world’s steel market.

Morgan had paid close attention to what Schwab said, and after the dinner, he took him aside to talk privately. Characteristically, Morgan decided to immediately pursue Schwab’s vision. Both he and Schwab knew Carnegie’s agreement was key to the deal.

Schwab went to see Carnegie at a cottage Carnegie maintained at St. Andrews Golf Course north of New York City, and over a game of golf, Carnegie agreed to sell U.S. Steel to Morgan for $492,000,000. When Carnegie shook hands with Morgan later, the latter said, “Congratulations on becoming the richest man in the world.” Carnegie had come a long way from his first job as a bobbin boy making $1.20 a week.

Carnegie spent the last two decades of his life giving away 90 percent of his fortune. Beginning in 1880, he built more than 2,500 libraries in the United States, Canada, Britain, and elsewhere. The first, not surprisingly, was in his hometown of Dunfermline, Scotland. By the time of his death in 1919, about half the public libraries in the United States had been built by Andrew Carnegie.

Carnegie libraries, like this one in Littleton, New Hampshire, were built to fulfill Andrew Carnegie’s sense of social responsibility and provide access to education for generations to come.

Carnegie libraries, like this one in Littleton, New Hampshire, were built to fulfill Andrew Carnegie’s sense of social responsibility and provide access to education for generations to come.Carnegie also established the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, which operates four museums in that city; the Carnegie Technical Schools, now part of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh; and Carnegie Hall for classical music performances in New York. His most generous gift, of $120 million, was given to establish the Carnegie Corporation of New York, one of the earliest and still one of the biggest philanthropic foundations in the United States.

Review Questions

1. Which statement about Andrew Carnegie and J. P. Morgan is correct?

- Carnegie was born into a wealthy family and Morgan was not.

- Both men were from wealthy families.

- Both men lived “rags to riches'” stories.

- Morgan was from a wealthy family and Carnegie was not.

2. Andrew Carnegie successfully used what strategy to build the most successful steel company in the world?

- He resisted risky business innovation to stick with proven methods.

- He reinvested all his profits in business expansion as quickly as possible.

- He used consolidation to gain control of raw materials and reduce competition.

- He made wise investments with the family fortune he inherited.

3. To whom did Andrew Carnegie sell U.S. Steel?

- Edward Jones

- John D. Rockefeller

- Charles Schwab

- J. P. Morgan

4. Which most accurately describes Andrew Carnegie’s charitable contribution to American society?

- He left most of his fortune to his family and used the rest to build a university dedicated to medical studies.

- He set aside some of his fortune for the public welfare, mainly in education.

- He spent most of his fortune building libraries and museums and endowing other philanthropic endeavors.

- He bequeathed college scholarships to the children of his employees.

5. The business model Andrew Carnegie used to build his successful steel empire consisted of

- hostile takeovers of weaker businesses

- vertical integration

- horizontal integration

- both vertical and horizontal integration

6. Andrew Carnegie put forth his philanthropic beliefs in his famous work entitled

- “The Gospel of Wealth”

- Poverty and Progress

- “The Talented Tenth”

- The Jungle

Free Response Questions

- Describe the business strategy Andrew Carnegie used to amass his great fortune.

- Explain how Andrew Carnegie was able to transform the American steel industry.

AP Practice Questions

“Thus is the problem of rich and poor to be solved. The laws of accumulation will be left free, the laws of distribution free. Individualism will continue, but the millionaire will be but a trustee of the poor, entrusted for a season with a great part of the increased wealth of the community, but administering it for the community far better than it could or would have done for itself. The best minds will thus have reached a stage in the development of the race in which it is clearly seen that there is no mode of disposing of surplus wealth creditable to thoughtful and earnest men into whose hands it flows, save by using it year by year for the general good. This day already dawns. Men may die without incurring the pity of their fellows, still sharers in great business enterprises from which their capital cannot be or has not been withdrawn, and which is left chiefly at death for public uses; yet the day is not far distant when the man who dies leaving behind him millions of available wealth, which was free to him to administer during life, will pass away ‘unwept, unhonored, and unsung,’ no matter to what uses he leaves the dross which he cannot take with him. Of such as these the public verdict will then be: The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced.'”

Andrew Carnegie, The Gospel of Wealth, 1889

Refer to the excerpt provided.1. Andrew Carnegie’s motivation for writing the excerpt was that he believed the rich

- had a philanthropic responsibility to help those who were less privileged

- had a right to maintain their fortunes, as long as they were earned honestly

- needed to invest in business to create more jobs for Americans

- should provide a minimum income for all Americans

2. Which of the following groups would support the concept of helping the poor as expressed in the excerpt?

- The Populists

- The National and American Women’s Suffrage Association

- The Bull Moose Party

- Settlement house workers

3. Factors that allowed people like Andrew Carnegie to amass a large personal fortune in this era included the

- profits made by a few individuals during the Civil War

- Industrial Revolution’s new technologies and processes

- scandals that occurred during the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

- profits made from land speculation during the period of Manifest Destiny

Primary Sources

Carnegie, Andrew. “Gospel of Wealth.” North American Review 148 (June):653-665.

Carnegie, Andrew. “Carnegie Speaks: A Recording of ‘The Gospel of Wealth.” http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5766/

Carnegie, Andrew. “Wealth.” June 1889. https://www.swarthmore.edu/SocSci/rbannis1/AIH19th/Carnegie.html

Suggested Resources

Brands, H.W. Masters of Enterprise: Giants of American Business from John Jacob Astor to Bill Gates and Oprah Winfrey. New York: Free Press, 1999.

Chernow, Ron. The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance, New York, Grove Press, 1990.

Livesay, Harold C. American Made: Men Who Shaped the American Economy. Boston: Little, Brown, 1980.

Livesay, Harold C. Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business. Boston: Little Brown, 1975.

Krass, Peter. Carnegie. New York: John Wylie and Sons, 2002.

Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Penguin, 2006.

Strouse, Jean. Morgan: American Financier. New York: Random House, 1999.

Wall, Joseph Frazier. Andrew Carnegie. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989.