Chapter 9 Introductory Essay: 1877-1898

Written by: LeeAnna Keith, The Collegiate School

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the historical context for the rise of industrial capitalism in the United States

Introduction

The late nineteenth century saw the rapid growth of the American economy as technological developments and immigration led to the rise of an industrial, mass-production society. American capitalism drew on the country’s vast natural resources, the ready supply of laborers, and the expertise and determination of a new class of industrialists. Railroads provided a powerful medium for wealth creation, giving rise to the modern corporation, innovations in finance, and increasing demand for steel, machinery, oil, and laborers of all kinds. As railroad networks expanded, the cost of freight plummeted, creating opportunities for national distribution networks, new consumer-driven industries, and the emergence of advertising and national brands (see The Transcontinental Railroad Narrative).

The development of American industry led, in turn, to the creation of a mass society. Markets were increasingly linked by railroads. Migrants from the countryside and immigrants from abroad flooded growing cities in search of opportunities. Rising wages and falling prices benefitted the millions who now had more disposable income. Urban society and improvements in communication spawned a mass national and consumer culture.

This period of national economic expansion faced numerous challenges as well. Certain railroads and businesses merged into monopolies and became powerful enough to control entire industries for their own benefit or to destabilize financial markets. Affected interest groups pressured the federal government to regulate railroads and corporations. As railroads navigated the new regulatory environment, they continued to enlarge the economy and reorganize the physical landscape.

The American economic and social landscape was changing. Large cities were crowded with new arrivals, leading to widespread poverty, pollution, and disease. Local and state government services were virtually nonexistent. Conditions in factories were often dangerous and unhealthy for employees. Millions of unskilled workers still lived on the edge of poverty and under the constant threat of unemployment or industrial accident. Contention was rife during worker strikes, farmer revolts, recessions, and attempts to restrict immigration. The end of Reconstruction left African Americans in a precarious position due to sharecropping, legal segregation, denial of civil rights, and violence that frustrated the promises of equality. Women struggled for equality and the right to vote in states and nationally.

The period from the Civil War to the turn of the twentieth century became known as the “Gilded Age” because the United States became an industrial powerhouse with rapidly expanding national wealth. However, underneath the gilded surface, the period presented Americans with many challenges that shaped the course of twentieth-century American history.

The Rise of Big Business

Steel, oil, and machinery magnates emerged as innovators of historical importance, pioneering new production methods and technology that transformed the daily life of nineteenth-century Americans. Andrew Carnegie introduced into his steel factories numerous technological innovations that drove down the price of steel, giving his company a competitive advantage over rivals that led it to dominate the steel industry and indirectly benefit consumers via lower prices (see the Andrew Carnegie and the Creation of U.S. Steel Narrative). Telephone service began its rise to prominence during the Gilded Age, thanks to Boston-based researcher Alexander Graham Bell. Thomas Edison, called the “Wizard of Menlo Park” in a reference to his New Jersey laboratory, introduced the possibilities of electrification and other forms of energy, recorded sound, moving pictures, and other inventions for mass production and consumerism. Nikola Tesla, an immigrant from Croatia, made several inventions in electricity, motors, and wireless communications. Combined with the telegraph, these inventions led to a communications revolution and tied distant markets together. The technological innovations also created economies of scale that allowed corporations to produce goods more efficiently and less expensively.

This photograph probably from 1878 shows Thomas Edison with one of his first inventions the phonograph.

Practicing the management and efficiency techniques formulated by Frederick Winslow Taylor, industrialists demanded greater productivity from their factory workers, who faced increasingly strict management of their time and activities. In the field of finance, entrepreneurs, faced with increasing competition and falling prices, pushed to eliminate rivals and streamline operations. Businesses used vertical integration to gain control over all the stages of production, distribution, and sales in order to lower prices. This helped build corporations that stretched across the continent, like Gustavus Swift’s integrated meatpacking company. Another variety of corporate giant pursued horizontal integration, buying out or crushing competitors and organizing monopolistic trusts and cartels. For example, John D. Rockefeller set the bar for both forms of consolidation, integrating Standard Oil vertically and horizontally to gain control over 90 percent of the oil industry. American industries faced cutthroat competition globally as well as at home. The Russians discovered massive deposits of oil, and the American share of the world’s refined oil dropped from 85 percent to 53 percent during the 1880s. Standard Oil made additional technological innovations to lower prices and recover its position in foreign markets.

In response to the rise of big business and the consolidation of the economy, farmers, journalists, workers, reformers, and even small and large businesses called for increasing state and federal regulation of business. States and, later, the national government moved to impose oversight of the railway industry, including the regulatory policies upheld by the Supreme Court decision in Munn v. Illinois (1877) and by the Interstate Commerce Commission (established in 1887). In 1890, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act to prevent “every . . . combination . . . in restraint of trade or commerce among the several states.” However, in 1895, with its ruling in U.S. v. E.C. Knight, a case involving a sugar refining monopoly, the Supreme Court decided the antitrust law was too vague and did not apply it to the sugar trust, because the trust’s activity was rooted in manufacturing rather than in interstate commerce. The Supreme Court thus effectively rendered the Sherman Act unenforceable in most cases. Judges sometimes issued Sherman Act antitrust injunctions on labor organizing as a monopolistic practice, because of the closed shop that forced all workers to join the union. Corporations invested in political alliances, cultivating business-friendly government during an age of corruption.

The rise of advertising and the convenience and thrill of new offerings from elaborate urban department stores and mail-order catalogs for rural inhabitants led people to increase their consumption of mass-produced goods. Consumers also had access to easier credit to purchase items they could not previously afford. The Victorian culture of thrift and industry was gradually replaced by a consumer culture of spending for immediate gratification.

At the same time, business owners also advocated effectively on behalf of their own public images. They sincerely believed in the Gospel of Wealth, which preached that the affluent had a responsibility to provide charity to the poor and social uplift to the masses with middle-class culture. Many leaders of big business donated hundreds of millions of dollars to philanthropic causes such as libraries, concert halls, and museums (see the Were the Titans of the Gilded Age “Robber Barons” or “Entrepreneurial Industrialists”? Point-Counterpoint).

The hardships of the poor were aggravated by deep and successive depressions, first in 1873–1878 and then more painfully in 1893–1897. Millions of workers experienced unemployment and poverty during these recessions and depended on private charity because there was no unemployment insurance or similar programs. However, the real wages of all workers rose 44 percent from the end of the Civil War to World War I; they benefitted from higher wages and lower prices (deflation). Moreover, skilled workers commanded much higher wages and job security than unskilled industrial workers.

Several writers published critiques of the Gilded Age’s social order, including Edward Bellamy who wrote Looking Backward, a utopian novel in which a future American economy was purged of its problems (see the Edward Bellamy, Looking Backward, 2000−1887, 1888 Primary Source). Henry George’s Progress and Poverty issued a proposal for a 100 percent tax on gains in the value of land in order to redistribute wealth for the public good (see the Debating Industrial Progress: Andrew Carnegie vs. Henry George Lesson). The most direct challenge to the capitalist order, however, emerged from the ranks of industrial employees, who began to organize into unions.

Watch this BRI Homework Help video on entrepreneurs for a summary of the men of big business and their effect on society.

Workers and Unions

The industrial factory system changed the nature of work from the agricultural and artisan pace of the early nineteenth century. It also caused a great deal of suffering for millions of workers in factories by demanding conformity to wage and work schedules that maximized output and profits. Employees labored in factories polluted by noise and filth and risked hazards to life and limb, such as those that resulted in the death or injury of one in four Pennsylvania steelworkers. Women and children in the workforce often had low-paying and dangerous jobs in factories and mines.

As a result, during the Gilded Age, unions staged a bid for more control of the workplace, along with higher wages and shorter hours. Unions conceived of the strike, or work stoppage, and used its power to attempt to win those concessions from business owners. This movement began with the Great Uprising of 1877 or Great Railroad Strike, a nationwide railway strike. Railroad workers found unity across craft and geographic lines, forming the first U.S. industrial union and deploying boycotts and sympathy strikes. The largest union of the 1870s and 1880s was the Knights of Labor, which was inclusive of most workers and had a utopian vision of a cooperative society. An alternate form of organizing, practiced by the American Federation of Labor after 1886, divided workers by their specific crafts and favored skilled, white, male, and, often, native-born laborers, because this gave the union greater bargaining power and organizational strength. Unions generally confronted hostile judges who issued injunctions to interrupt their activities.

Maryland’s National Guard had to fight its way through a mob during the Great Uprising of 1877.

Great eruptions of industrial violence occurred during the Gilded Age. Governors and even presidents routinely called out troops to suppress strikes and prevent violence. Owners hired private armies such as agents of the Pinkerton Detective Agency to battle striking workers. But troops, workers, and private armies all contributed to these violent confrontations. During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, hundreds were killed and injured by violence. A Chicago strike in May 1886 led to a few deaths near a McCormick agricultural machine factory and to an anarchist bombing and shoot-out with police officers. The Homestead Steel Lockout of 1892 resulted in dozens of deaths and injuries when strikers and Pinkerton guards battled before the state militia was called in (see The Homestead Strike Narrative). During the 1894 Pullman Strike, striking workers set buildings on fire and destroyed or derailed hundreds of railway cars. More than 14,000 state militia and federal troops were called to restore order after national guardsmen killed 34 strikers. During the strike, officials citing the anti-conspiracy properties of the Sherman Antitrust Act jailed the American Railway Union’s founder, the socialist Eugene Debs.

The West

Millions crossed the Mississippi River in the late nineteenth century, using rail transportation and claiming land under the 1862 Homestead Act to take advantage of celebrated opportunities in the West. This migration relieved some of the pressures of urban and town life in the East. Moreover, according to historian Frederick Jackson Turner, the pioneer experience epitomized and shaped what became the American ethos of individualism and self-reliance (see the Frederick Jackson Turner, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History,” 1893 Primary Source). Resourceful individualism and courage in the face of danger and hazards of the frontier had made America great, according to Turner’s thesis (see the Was Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis Myth or Reality? Point-Counterpoint). In addition to the individual efforts of millions of settlers, the federal government played a pivotal role in smoothing the way for westward migration through policies aiding railroads and distributing public lands for development. Such policies stimulated the western economy in the late nineteenth century, particularly for newly established farmers, miners, and ranchers.

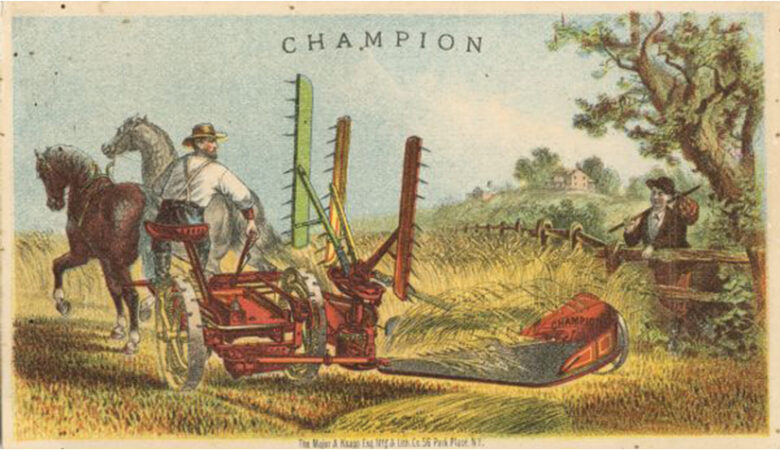

Western economics, like industrial development, favored agglomeration. The mechanization of agriculture (by means such as the McCormick Harvesting Corporation’s machine reaper) transformed farming, making it an increasingly capital-intensive enterprise. Accordingly, family farms assumed debt to compete with the productivity of mechanized rivals, many of whom established large “bonanza” farms employing migrant laborers. Though technology offered the advantages of irrigation and large-scale plowing, it could not insulate western farmers from environmental hazards, including historic droughts, pestilences, and conflicts with Indians. By the 1890s, most bonanza farms had broken up into smaller enterprises that could better handle the boom-and-bust cycles of farming. Individual pioneers of western mining, including the prototypical rugged mountain prospector, had discovered gold, silver, and industrial minerals in the region. Though many had prospered, the late nineteenth-century trends generally favored big conglomerations, even in the West.

This depiction of a harvesting reaper from 1875 demonstrates how agriculture was transformed by mechanization.

Ranchers seemed to epitomize the independence celebrated by the Turner thesis, but Gilded Age capital was critical to their success. In the decades after the Civil War, ranchers delivered millions of cattle on the hoof to the railway outposts of Chicago slaughterhouses, where the animals were processed and distributed nationally by Swift and other meatpacking companies (see the Cowboys and Cattle Drives Narrative). The advent of barbed wire drastically reduced the cost of enclosing wide tracts of land and hastened the decline of small-scale ranching dependent on cowboy labor. In its place, an agribusiness model of cattle raising took root in California and the plains states.

Migration and capitalism transformed the physical and cultural landscape of the West. Bison herds numbering in the tens of millions had helped form the grasslands in the heart of the continent, and their diminishing numbers in the 1870s and afterward created major ecological and social changes. Bison disappeared along with open ranges, as barbed wire and railroads divided the land. They were also the targets of deliberate depopulation, shot from passing trains and left to rot, or killed and processed in a frenzy for their hides. By the 1890s, the once-mighty bison population stood at the brink of extinction, resulting in a last-minute intervention by conservationists to save the species.

American Indians

The destruction of the buffalo hurt the plains tribes that depended on the animals for food and furs. It also dovetailed with broader pressures to reduce the autonomy of American Indians in the West, many of whom became embroiled in a final series of military conflicts. By the late nineteenth century, western Indians existed in a shrinking area of traditional autonomy. The Sioux, Arapaho, and other nations of the Northwest were signatories of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, an agreement that introduced tribal reservations and annual payments by the federal government in exchange for lands ceded to settlers and guarantees of safe passage for migrants. Older treaties offered recognition to certain native populations in Indian Territory, including transplants such as the Cherokee and other formerly southeastern and Great Lakes tribes. In the Southwest, federal authorities struggled to contain nomadic Apache and Comanche peoples on substandard desert reservations, resorting to armed expeditions in search of dissident bands such as Geronimo’s Chiricahua Apaches. Troops engaged American Indians in several key battles, including the 1876 Sioux defeat of General Custer at Little Bighorn and the army’s massacre of Lakota families at Wounded Knee in 1890 (see the George Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn Narrative).

Government and philanthropic organizations urged Indians to assimilate into the American mainstream. The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 was intended as a “mighty pulverizing engine to break up the tribal mass,” as Theodore Roosevelt described it. By authorizing the allotment of tribal lands, the legislation purported to make landholders and U.S. citizens of American Indians who accepted 160-acre lots (see The Dawes Act, 1877 Primary Source). Instead, whites became the holders of many of the most valuable Indian lands while American Indian nations became poorer. Alongside this economic and political assault, white reformers initiated a campaign for cultural assimilation by education, establishing boarding schools for American Indian children, such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, where traditional dress and the speaking of native languages were prohibited and seminomadic tribes were forced to settle on poor lands (see the Images from the Carlisle Indian School, 1880s Primary Source).

This poster advertising the sale of American Indian land aimed to encourage American Indians to assimilate into U.S. culture by encouraging them to own and farm land.

Immigration

Between 1880 and 1920, nearly 23 million immigrants came to the United States from Europe, Asia, and Mexico in search of opportunity and freedom from persecution (see the Industry and Immigration in the Gilded Age Lesson). They moved to cities primarily, working in factory jobs and living in poorer, overcrowded neighborhoods. New arrivals from Europe, Asia, and the North American countryside toiled alongside native-born city dwellers, sharing urban experiences with strangers even while many chose to reside in ethnic enclaves. Immigrant communities emerged in urban, ethnic enclaves of Chinatowns or Little Italys that offered support networks and familiar foods, language, and worship opportunities. Urban elites invested in charitable programs designed to hasten the Americanization of new immigrants, among them reformer Jane Addams, whose Hull House provided services such as English-language classes, child care, and instruction in civics (see the Jane Addams, Hull House, and Immigration Narrative).

White, Protestant Americans extended the same assimilation programs to arriving European immigrants as a process of Americanization. State-based compulsory public education emerged as another way of Americanizing new arrivals. However, several groups who advocated for nativism organized groups that sought to restrict Eastern European immigration, especially through the use of literacy tests. Racial theories such as Social Darwinism reinforced ideas about Anglo-Saxon superiority, partially in response to anxiety about the country’s increasing racial and cultural diversity (see the Cartoon Analysis: Immigration in the Gilded Age, 1882−1896 Primary Source).

Certain groups were deemed beyond assimilation and were excluded from the body politic. Chinese and Japanese Americans faced extreme discrimination. Migrants and native-born Asian Americans alike were banned from voting and owning land, subject to discriminatory commercial licensing requirements, and threatened with physical assault and murder. Workers and unions also supported restrictions on immigration to reduce competition for jobs. In 1882, Congress passed the first-ever immigration restriction, banning the entry of nearly all Chinese laborers (see The Chinese Exclusion Act Decision Point).

This political cartoon of 1882 showing a Chinese immigrant barred from entering the United States is captioned “We must draw the line somewhere you know.”

African Americans

Also during the Gilded Age, African Americans in the South endured the emergence of the “Jim Crow” system. The progress and political gains made possible by post–Civil War constitutional amendments and Reconstruction soon regressed after a series of Supreme Court decisions and tactical victories by white supremacists. The first element of the unraveling was white violence, enabled by the retreat of the federal government from its role as the defender of black citizenship. By the 1880s, the terror conducted by the Ku Klux Klan and other groups after the end of Reconstruction had suppressed black voter participation to less than one-third of age-eligible men. Having seized control of politics, white southerners passed discriminatory laws, the worst of which aimed at the economic and political subjugation of black neighbors. A segregated and unequal public education system offered black students little opportunity to advance. Jim Crow laws and practices, such as segregation on railway cars and other accommodations, also attached daily humiliations to African Americans’ public life (see the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) Narrative, the Ida B. Wells and the Campaign against Lynching Narrative, and the Ida B. Wells, “Lynch Law,” 1893 Primary Source).

African Americans responded creatively to the challenge of economic and political subordination. One school of thought among black intellectuals argued for making progress in the South by building up black resources and skills. The leading figure of this so-called accommodationist approach was Booker T. Washington, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, which specialized in agricultural and mechanical instruction and inspired a wave of college and university development that white southerners tended to support (see the Booker T. Washington, “Speech to the Cotton States and International Exposition,” 1895 Primary Source). An alternate view was urged by W. E. B. Du Bois, who championed the idea that African Americans demand equal opportunity, civil rights, liberal arts education, and an end to discrimination (see the Debating Strategies for Change: Booker T. Washington vs. W.E.B. DuBois Lesson). Du Bois became the first black recipient of a doctoral degree from Harvard, wrote groundbreaking sociological studies of the black experience, and helped establish the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Finally, a third way encouraged the migration of African Americans out of the South to destinations in the West, in Africa, and in northern cities.

W. E. B. Du Bois photographed in 1918 was a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and an early advocate of African American civil rights.

Watch this BRI Homework Help video about African Americans in the Gilded Age for an overview of how African Americans experienced the period.

The Growth of Cities

The appeal of urban life in the late nineteenth century drew Americans of all races and backgrounds. Jobs provided the main attraction. Cities and factory towns employed a mostly unskilled workforce. In addition, a growing middle stratum of office workers served as clerks and managers in increasingly complex corporate enterprises.

Cities were overwhelmed by the millions of people arriving from the countryside or abroad. Many lived in dangerous and unhealthy tenement buildings. Streets were teeming with garbage, and water supplies carried cholera and other diseases. Reformers pressed for improved rail-car transportation, sanitation, and clean water.

Reformers like Jacob Riis exposed the unhealthy and often shocking living conditions of immigrant families. This 1889 photo is entitled “Lodgers in a Crowded Bayard Street Tenement.” Riis’s photographs of New York City slums inspired reforms in housing and sanitation.

Led by the Democrats, political parties reached out to immigrants and new urbanites of all kinds with help finding jobs, housing, and medical care. As arrivals navigated their new environment, they welcomed the offer of assistance from the ward bosses who dominated local government and from other party officials. Over time, these charitable functions boosted the formation of urban political machines, the most famous of which was New York City’s Democratic Tammany Hall organization (see the William “Boss” Tweed and Political Machines Narrative). The political machines, however, were infamous for their corruption, trading favors for votes and raking in millions from manipulating their offices (see the Were Urban Bosses Essential Service Providers or Corrupt Politicians? Point-Counterpoint). Starting in the 1870s, exposés by journalists and civil service reform at the national level, including the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883, challenged corrupt practices at every level of government by filling some government jobs with civil service workers, rather than with appointees through the patronage or “spoils system” of the victors of an election (see the Cartoon Analysis: Thomas Nast Takes on “Boss” Tweed, 1871 Primary Source).

This 1871 political cartoon by Thomas Nast depicts “Boss” Tweed one of the leaders of New York’s Tammany Hall as greedy and corrupt.

Politics

Advocates of political reform operated mostly outside the two-party system; for example, the farmers who formed the People’s Party movement of the 1890s and the members of the women’s suffrage movement. High voter turnout and elevated partisanship among Democrats and Republicans characterized the period after the Civil War, but the major party platforms differed little on ideological and policy issues; both parties were reluctant to alienate voters and about equally beholden to corporate interests. Disputes surrounding free trade and protectionism provided one point of contrast, with pro-manufacturing Republicans such as President William McKinley campaigning for high tariffs to keep jobs in the Northeast, and farmer-friendly Democrats campaigning as free traders. Grover Cleveland was the only Democratic president of the era, riding anti-tariff sentiment to two nonconsecutive terms in the White House.

Farmers and Populism

The business-friendly orientation of the major parties created an opening for the rise of the most ambitious third-party movement in American history to date: the People’s Party, or the Populists (see the Ignatius Donnelly and the 1892 Populist Platform Narrative). Populism had its origins among disgruntled farmers, for whom post–Civil War “grange” organizations had offered a platform to critique what they perceived to be the oppressive role of banks and railroads in agricultural life. Farmers often blamed big business for a long-term decline in the prices they received for their goods. They tried to form grange cooperatives to market their goods together and drive up the prices for them.

Posters like this one were used to promote The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry or “The Grange” for short.

In the 1870s and 1880s, the Farmers’ Alliance denounced the concentration of wealth and power, advocated the regulation and nationalization of railroads and banks, and called for the inflationary free coinage of silver. In the 1890s, the Populists continued to push for these reforms and tried to make common cause with industrial workers, demanding reforms such as currency inflation, which would ease the burden of debtors, and the eight-hour workday, a consistent demand of factory laborers (see the Populists and Socialists in the Gilded Age Lesson). Many white Populists in the South proved willing to seek cooperation with African American tenant farmers—a gesture of solidarity that underscored the radical possibilities of political realignment. The alarmed establishment took note and struck back by tightening voter qualifications and rewriting some state constitutions to exclude poor whites as well as blacks.

The Populists fused with the Democrats in 1896, when they nominated Democrat William Jennings Bryan to run for president. Bryan, like the Populists a supporter of bimetallism or “free silver,” warned big business and other supporters of the gold standard, “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold” (see the William Jennings Bryan, “Cross of Gold” speech, 1896 Primary Source). He lost the election, but farmers achieved most of their goals because Congress passed business regulations, and farm prices rose due to a general inflation at the turn of the century.

Foreign Policy

Initial moves toward establishing an overseas American empire served national strategic and economic interests. Ideas about racial superiority, and the civilizing mission of Social Darwinists who saw non-Western peoples as inferior and in need of uplift, also played a role. Many Americans and Europeans saw it as their duty to civilize other races around the globe. U.S. missionaries carried the flag to distant locations and petitioned the government to support military and economic missions in East Asia, West Africa, and the Pacific. Missionaries-turned-investors sponsored the Hawaiian Revolt of 1887–1893, installing the Christian fruit-grower Sanford B. Dole as president of a newly proclaimed Hawaiian Republic (see the The Annexation of Hawaii DBQ Lesson and the The Annexation of Hawaii Narrative).

Elsewhere, U.S. business interests played a role in the politics of several countries, buying up Native American land and railroads in Mexico and initiating profitable sewage, telephone, and electrical infrastructure projects in Havana and other Latin American capitals. This investment paved the way for expansion in the early twentieth century in the wake of the Spanish-American War. “We must dare to be great; and we must realize that greatness is the fruit of toil and sacrifice and high courage,” insisted Theodore Roosevelt in a militant speech of 1898. “Let us live in the harness, striving mightily,” the future president said.

The United States experienced industrialization, immigration, and urbanization during the late nineteenth century. The rapid change led to dramatic economic and demographic growth across the country as a national market was linked together and a quickly increasing population moved in search of opportunities. The United States expanded to become a global power through trade, acquisition of territory, and increased military might, which caused considerable debate about the course of American foreign policy. Progress was at times uneven and unequally distributed, which contrasted sharply with the vast wealth accumulated by leading industrialists. Some social groups suffered discrimination and did not fully participate in American civic life. Contests and disputes in American society during the Gilded Age caused businesses, labor unions, farmers, and other groups increasingly to look to the national government to expand its rule in the regulation of the economy. The dawn of the twentieth century presented continued opportunities for expansion at home and abroad, as well as new challenges.

The Gilded Age saw tremendous economic changes brought on by industrialization and urbanization leading to questions about the regulatory role of government. Debate over the treatment of groups within the United States continued as the twentieth century began.

Additional Chapter Resources

- The Brooklyn Bridge Narrative

- Grover Cleveland’s Veto of the Texas Seed Bill 1887 Primary Source

- Unit 5 Civics Connection: Civil Rights and Economic Freedom Lesson

Review Questions

1. The high rate of voter participation in the late nineteenth century existed

- because the major parties disagreed about how to handle strikes and labor organizing

- despite the fact that the major parties did not have significant policy differences

- because of the success of the Democrats in controlling the office of president

- as a result of an increase in African Americans exercising their voting rights

2. The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887

- established the Carlisle Indian Industrial School

- sought to end tribal identity by parceling and redistributing reservation land

- sought to eliminate controversy by parceling and redistributing reservation land

- abolished the Indian reservations in the West

3. What industry had the most significant impact on the development of industrialization in the United States in the late nineteenth century?

- Agriculture

- Export of U.S.-made products

- Railroads

- Textiles

4. Andrew Carnegie is most closely associated with which event?

- The invention of the telephone

- The revolution in the American agricultural industry

- The passage of the Interstate Commerce Act

- The growth of the American steel industry

5. The business innovations of Gustavus Swift took place in

- integrated meat packing

- time management in the workplace

- the mass production of communication devices

- the improvement of agricultural machinery

6. Vertical integration in business is best described as

- control of all aspects of an industry from origin to distribution in the marketplace

- control of the marketplace for a particular industry

- a monopoly on taking raw materials and producing them into textiles

- the ability to combine diverse industries into one major corporation

7. Which industrialist was known for using both vertical and horizontal integration in consolidating his business?

- Gustavus Swift

- John D. Rockefeller

- Frederick Winslow Taylor

- Andrew Carnegie

8. The main focus of the Sherman Antitrust Act was to

- control the activities of labor unions

- prevent deceptive advertising

- force states to regulate big businesses

- break up business monopolies

9. A strategy industrialists used to counteract their negative public image was to

- sponsor more immigrants to work in their factories

- provide comfortable housing for their employees

- provide free education for the children of their employees

- invest in popular philanthropic causes

10. Which statement best describes the change in the nature of work in the United States during the nineteenth century?

- The factory system required workers to conform to schedules that maximized efficiency.

- Employers accepted the development of labor unions and provided more benefits for their employees.

- The workplace became safer and more conducive to productivity because of new opportunities for personal connection between workers and managers.

- The age of artisan specialization began.

11. Opposition to economic consolidation by big business in the late nineteenth century was manifested in what way?

- The banning of labor unions

- Demands for regulatory laws

- The Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. v. E.C. Knight

- Government action to prevent work stoppages such as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877

12. The progress of labor unions during the late nineteenth century can be described as

- greatly encouraged by the federal courts

- supported by the Pinkerton Detective Agency

- hampered by government officials at the state and federal level

- enhanced by successful labor strikes

13. What change in policy had the least significant effect on the development of the American West?

- The invention of barbed wire

- The relocation of American Indians to reservations

- The presentation of the Turner thesis

- The almost complete destruction of the buffalo on the Great Plains

14. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 was the first treaty that

- guaranteed a peaceful coexistence between the Federal government and American Indians

- called for the placement of American Indians on reservations

- led to the end of the Indian Wars

- ultimately resulted in the defeat of the U.S. Calvary at the Battle of the Little Bighorn

15. The concept of Social Darwinism influenced which trend in the United States during the late nineteenth century?

- The growth of labor unions

- The justification of the “superiority” of white Anglo-Saxon Protestants

- Arguments against imperialism

- The rise of the Populists in American politics

16. Life in the South in the 1880s was more difficult for African Americans than during the period of Radical Reconstruction due to

- the passage of Jim Crow laws

- increased industrialization

- the activity of the Ku Klux Klan

- the Reconstruction Amendments

17. How did many African Americans who supported the ideas of Booker T. Washington respond to Jim Crow laws in the South?

- African Americans formed agriculturally based unions and used the strike to achieve their demands.

- Many became accommodationists learning a trade to earn a living and become economically independent.

- African Americans started a radical civil rights movement.

- African Americans in the South became sharecroppers and refused to interact with white society.

18. The most significant factor that brought European immigrants to the United States during the late nineteenth century was

- better living conditions

- political freedom

- jobs resulting from the industrial revolution

- religious freedom

19. Disgruntled farmers in the North and the South reacted to unresponsive federal policies of the late nineteenth century by

- forming a new political party

- protesting the lack of Republican leadership on agricultural issues and joining the Democratic Party

- going on strike against the railroad industry

- demanding the Federal government subsidize their farms

Free Response Questions

- Analyze the effect of organized labor’s battles with management over wages and working conditions during the Gilded Age.

- Analyze the reasons various groups migrated to the North American West between 1840 and 1890.

- Describe the responses of African Americans to the social and political changes of the late nineteenth century.

- Explain the motivations behind the development of the Populist movement.

AP Practice Questions

The text in this political cartoon from 1871 reads “The Ballot. In Counting There Is Strength.” The text beneath the image reads “That’s What’s The Matter.” Boss Tweed. “As long as I count the votes what are you going to do about it? Say?”

1. The context illustrated by the political cartoon was

- Jim Crow laws preventing African Americans from voting in the South

- corrupt elections in major cities run by political machines

- large industries controlling the vote

- farmers losing their majority in the House of Representatives

2. Which of the following groups would most strongly agree with the criticism embodied in the political cartoon?

- Populists

- Suffragists

- African American civil rights activists

- Civil service reformers

Within the image in this political cartoon from 1871 are such terms as “Coolie Slave Pauper and Rat-Eater” “The Chinaman works cheap because he is a Barbarian” Underneath the image is this text: “The Chinese Question. Columbia: “Hands off gentlemen! America means fair play for all men!”

3. The political cartoon most directly illustrates a government policy that

- restricted immigrants to certain jobs

- promoted reforms in helping the impoverished

- limited immigration of selected groups

- endorsed unlimited immigration

4. The illustrator of this political cartoon would most likely support

- unrestricted Chinese immigration

- a ban on political extremists immigrating to the United States

- anti-lynching laws

- the Populist Party platform

Primary Sources

Carnegie Andrew. “The Gospel of Wealth.” 1889. https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1889carnegie.asp

Hearing before the Committee on Woman Suffrage February 21 1894 53rd Cong. Senate. 2nd Session (1894). https://www.loc.gov/item/93838349/

Lodge Ella. “Come Join the Knights of Labor or The Railway Strike Song & Chorus.” 1888. http://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/collection/057/069.

Old Timers on the “Rosebud”: near White River South Dakota 1890. Photograph. North Dakota State University Libraries Institute for Regional Studies. http://digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw/id/3888/rec/10

Roosevelt Theodore. “National Life and Character.” August 1894. http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/national-life-and-character/

Washington Booker T. “Speech Before the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition.” September 18, 1895. http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/speech-before-the-atlanta-cotton-states-and-international-exposition/

Yick Wo v. Hopkins. 118 U.S. at 356 (1886). https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=2131565438211553011&hl=en&as_sdt=6&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr

Suggested Resources

Annenberg Public Policy Center. “Yick Wo and the Equal Protection Clause.” n.d. http://www.annenbergclassroom.org/page/yick-wo-equal-protection-clause

Brands H.W. American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism 1865-1900. New York: Doubleday 2010.

Chernow Ron. Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller Sr. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group 2007.

Cronon William. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: W. W. Norton & Company 2009.

Deloria Vine Jr. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press 1969.

Danosh Mona. American Commodities in an Age of Empire. Abingdon UK: Taylor & Francis 2006.

Hahn Steven. A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press 2003.

Hays Samuel P. The Response to Industrialism 1885-1914. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1995.

Huhndorf Shari. Going Native: Indians in the American Cultural Imagination. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press 2015.

Hunt Michael. Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy. New Haven CT: Yale University Press 2009.

Kessner Thomas. Capital City: New York City and the Men Behind America’s Rise to Economic Dominance 1860-1900. New York: Simon and Schuster 2004.

Limerick Patricia. The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West. New York: W. W. Norton & Company 2011.

Magoc Chris J. Imperialism and Expansionism in American History: A Social Political and Cultural Encyclopedia and Document Collection. New York: ABC-CLIO 2015.

Montgomery David. The Fall of the House of Labor: The Workplace the State and American Labor Activism 1865-1925. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press 1989.

Painter Nell. Standing at Armageddon: The United States 1877-1919. New York: W. W. Norton & Company 1989.

Sanders Elizabeth. Roots of Reform: Farmers Workers and the American State 1877-1917. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1999.

Schaller Michael et al. American Horizons: U.S. History in Global Context Volume II: Since 1865. New York: Oxford University Press 2016.

Slotkin Richard. The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in the Age of Industrialization 1800-1890. Norman OK: University of Oklahoma Press 1998.

Takaki Ronald. A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America. Boston: Little Brown and Company 2008.

Trachtenberg Alan. The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age. New York: Hill and Wang 2007.

Valelly Richard. The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2004.

Warner Sam Bass Jr. The Urban Wilderness: A History of the American City. Berkeley CA: University of California Press 1995.

Warren Louis S. Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group 2007.

White Richard. Railroaded: The Transcontinental Railroad and the Making of America. New York: W. W. Norton & Company 2011.

White Richard. The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age 1865-1896. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press 2017.

Wiebe Robert H. Businessmen and Reform: A Study of the Progressive Movement. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee 1988.

Wiebe Robert H. The Search for Order 1877-1920. New York: Hill and Wang 1966.