Eli Whitney and the Cotton Gin

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the continuities and changes in regional attitudes about slavery as it expanded from 1754 to 1800

- Explain the causes and effects of the innovations in technology, agriculture, and commerce over time

Suggested Sequencing

This Narrative should be assigned to students to help illustrate the expansion of cotton production and slavery in the South.

In 1792, Eli Whitney graduated from Yale and traveled south to Georgia to become a tutor for the children of Caty Greene, the widow of Revolutionary War hero Nathanael Greene. Whitney had been recommended for the post by Phineas Miller, manager of Greene’s plantation and an acquaintance of Whitney’s. Although the tutoring position did not work out, Greene did invite Whitney to stay at her plantation in Georgia as a guest. He appreciated her hospitality and contributed his mechanical skills to the repair of equipment around the farm and the fashioning of new devices to make tasks easier.

Eli Whitney is pictured here in an 1822 portrait by Samuel Finley Breese Morse.

One day, a group of veterans who had served under General Greene during the American Revolution came to the plantation for a visit. Mostly planters themselves, they lamented the state of agriculture in the South and voiced their frustration about the amount of labor it took for their slaves and laborers to remove the seeds from short-staple cotton. Because it took an entire day to separate the sticky seeds from only about one pound of cotton fiber, it was an unprofitable task. When one of the men wished there was a machine that could remove the seeds, Greene proposed that Whitney was the man to invent one.

The need was great because the planters desperately wanted to export more cotton to England, which was at the beginning of its market revolution. The textile factories with their spinning and weaving machines needed cotton as the raw material to produce their goods. If they could use a machine to process their raw cotton, the southern planters would have a newly profitable crop and could rejuvenate southern agriculture.

Whitney accepted Greene’s challenge to make a machine to remove cotton seeds and produced a crude but workable model of the “cotton gin” (gin being southern slang of the time for “engine”). He had had an idea that could transform the landscape and create great fortunes, but he did not have the money to develop, patent, and manufacture his invention. Whitney overcame this hurdle by entering into a partnership with Miller, who agreed to provide financial backing in return for a percentage of ownership in the proceeds.

Flush with Miller’s investment, Whitney headed north to secure a patent and begin manufacturing the cotton gin with the help of machine tools producing uniform parts. The potential for this invention excited even Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who wrote to Whitney in November 1793: “I feel a considerable interest in the success of your invention, for family use…Favorable answers to [my] questions would induce me to engage one of them to be forwarded to Richmond for me.” With such endorsements, Whitney was understandably anxious to get into business and anticipated great success.

Whitney applied for a patent in Philadelphia in October 1793 and was awarded one in March 1794. Instead of selling the machines (which were too expensive for most planters), Whitney and Miller planned to clean the cotton for a percentage of the crop. However, many imitators throughout the South stole Whitney’s idea and produced their own machines, violating his patent rights.

Whitney spent the next several years engaged in litigation to protect his invention. He had difficulty winning the lawsuits or collecting money, but his legal struggles led the cotton gin to pass into widespread use much faster than if he had had an exclusive right to the patent and no imitators. The enslaved workers of southern cotton planters processed incredible amounts of cotton with their cotton gins.

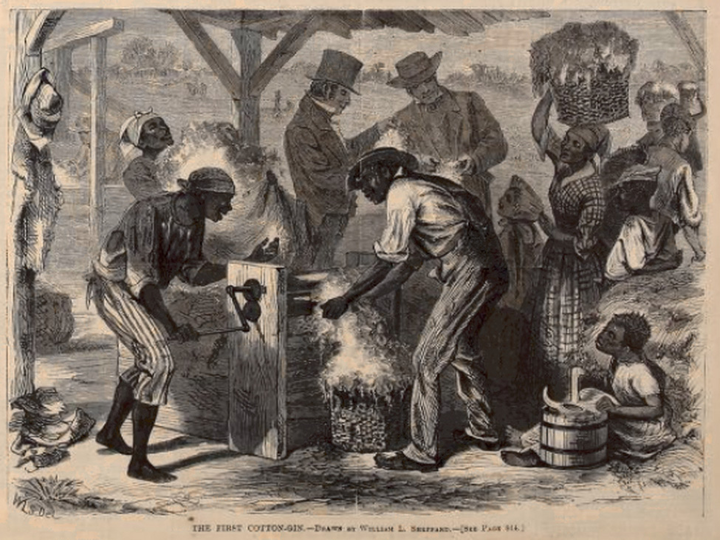

In this illustration from Harper’s Weekly in 1869, enslaved workers operate a cotton gin.

In 1812, Congress refused to renew Eli Whitney’s patent on the cotton gin, effectively putting him out of business. Whitney had lost the exclusive right to his invention, one that had transformed American agriculture. U.S. cotton exports had grown from less than 150,000 pounds before the cotton gin to more than 18,000,000 pounds by the turn of century.

The effects of the cotton gin on the American economy, the geographical expansion of the new nation, and the growth of slavery were staggering. For decades, tobacco had been a declining crop that depleted the soil in the Chesapeake region, but cotton grew well in the Lower South. Planters and their enslaved workers raised the cash crop to meet demand from British and northern textile factories. Within only a decade, by 1805, cotton production rapidly increased from two million pounds to more than sixty million pounds. By the 1830s, that number would increase exponentially to more than 500 million pounds annually and became the largest American agricultural export.

This graph shows the staggering effect of the cotton gin on increasing cotton production in the United States. (credit: “U.S. Cotton Production 1790-1834” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr, CC BY 4.0)

The cotton gin also dramatically affected the geographical expansion of the new nation. Cotton planters and their slaves moved to Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama to start new cotton plantations. Americans were driving into the frontier to the north in search of farm land for cotton and opportunity. Many southerners left the Atlantic Seaboard and moved west because of cotton’s new potential, and the Southwest grew dramatically thanks to new cotton plantations.

The effects on slavery and enslaved persons were significant. As planters in the Chesapeake region diversified their crops away from tobacco, they sold their slaves to cotton planters in the South. This created a massive interstate slave trade that transferred enslaved persons through auctions and forced marches in chains, and that also broke up many slave families.

The expansion of cotton helped fuel the growth of an interlinked market economy in the United States, including in the North, because of the subsequent expansion of textile manufacturing and demand for cotton there. However, the cotton gin also helped ensure the survival and growth of slavery in the United States. The contradictory forces of expanding freedom and spreading slavery had a dramatic impact on politics in the early republic. The addition of new states and the accompanying growth of power in Congress, sometimes for the North and sometimes for the South, created sectional tensions that were narrowly resolved through a series of compromises, beginning with the Missouri Compromise in 1819-1820. Meanwhile, national debates over protective tariffs and internal improvement related to the cotton economy caused sectional disputes and eventually threatened the survival of the Union.

Review Questions

1. Eli Whitney set out to

- invent a machine that would make the tobacco harvest more profitable

- end the need for cotton-based slave labor

- stimulate the textile industry and American industrial revolution

- create an easier method for processing cotton

2. On which of the following did the cotton gin have the most immediate significant impact?

- Slave labor

- Industrialization

- Westward expansion

- Trade

3. How did the invention of the cotton gin most significantly affect the economic development of North America?

- It inspired Americans to look outside their borders for colonial territory.

- It made the Atlantic Coast the center of growing world industrialization during the first half of the nineteenth century.

- It continued the development of the South as an agricultural region based on the plantation system and spurred the rise of the textile mills in the North.

- It encouraged the continued importation of slave labor from Africa and the Caribbean through the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

4. The invention of the cotton gin led to all the following during the first half of the nineteenth century except

- the geographic expansion of the United States

- a rapid growth in the need for slave labor

- an increased reliance on tobacco as a cash crop

- rapid growth in the American economy

5. The increased need for slave labor during the first quarter of the nineteenth century led to

- the rapid development of an abolitionist movement

- a growing debate over where slavery could exist in the United States

- slowed industrialization in the North

- a call to continue the importation of slave labor from Africa

6. What was the main incentive for the invention of the cotton gin?

- Soil was being rapidly depleted by tobacco and a more profitable crop was necessary.

- The slave population was growing rapidly and increased cotton production was required.

- Southern plantation owners needed to diversify to better use the crop rotation method.

- American planters wanted to profitably provide English textile mills with raw cotton.

Free Response Questions

- Describe the impact of the invention of the cotton gin on the southern economy in the first part of the nineteenth century.

- Identify and explain a significant long-term impact of the invention of the cotton gin.

AP Practice Questions

The First Cotton Gin appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1869. This image depicts a roller gin, which preceded Eli Whitney’s invention.

1. A major impact on the United States of the event depicted in the drawing was that

- the need for paid agriculture labor in the South decreased as machines replaced workers

- the Deep South became an almost exclusive one-crop economy

- northern politicians issued an immediate call for the abolition of slavery

- the United States became a world-leading industrial power

2. A significant long-term impact of the event depicted was that

- as the nation expanded westward, the southern states became more defensive of the institution of slavery

- the South supported higher tariffs to protect the cotton industry

- poor, uneducated whites began to plant and harvest cotton

- a factory system developed in the South to produce textiles

3. Which statement does the drawing best support?

- Slave labor is immoral and should be banned.

- The federal government initially supported the expansion of slavery into the western territories.

- The invention of the cotton gin increased the demand for slave labor.

- The development of technology in the late eighteenth century provided free blacks with economic opportunities.

The map shows the United States at the time of the Missouri Compromise in 1820.

4. Which best describes the changes shown in the map that occurred during the first quarter of the nineteenth century?

- Impact of Manifest Destiny

- Expansion of places where slavery could exist

- Rise of industrialization

- Admission of new states to the Union

5. A major controversy associated with the events depicted in the map stemmed from

- unresolved issues from the War of 1812

- the desire of Americans to occupy all of North America

- the Louisiana Purchase and the growing debate over slavery

- the shift of political power to western states

Primary Sources

Jefferson, Thomas. Letter to Eli Whitney. November 16, 1793. https://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj1.019_0956_0956/?st=text

Whitney, Eli. “Patent for a Cotton Gin.” 1794. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false&doc=14

Suggested Resources

Green, Constance M. Eli Whitney and the Birth of American Technology. Boston: Little, Brown, 1956.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What God Hath Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Livesay, Harold C. American Made: Men Who Shaped the American Economy. Boston: Little, Brown, 1979.

Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.