Students and the Anti-War Movement

Written by: Kenneth J. Heineman, Angelo State University

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain how mass culture has been maintained or challenged over time

- Explain how and why opposition to existing policies and values developed and changed over the course of the 20th century

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Protests at the University of California, Berkeley Decision Point; the Free Speech and the Student Anti-War Movement Decision Point; the Students for a Democratic Society, “Port Huron Statement,” 1962 Primary Source; and the Walter Cronkite Speaks Out against Vietnam, February 27, 1968 Primary Source to discuss the public dissent of the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War.

The baby boom generation came of age during the Cold War in an affluent economy. When they entered college in the early 1960s, some of the young people were influenced by reading the works of radical critics of postwar America. Those intellectuals questioned the Cold War foreign policy of communist containment and searched for meaning in corporate and suburban America, which they considered conformist. Three critical academics, in particular, had an enormous influence on college campuses during the 1960s: Columbia sociologist C. Wright Mills, Wisconsin historian William A. Williams, and Brandeis philosopher Herbert Marcuse. The intellectual foundation of the 1960s university protest against American foreign policy and the Vietnam War can be found in their books, articles, and lectures.

Mills believed a “power elite” ruled the United States. He contended that, behind the facade of reform during the Great Depression, federal bureaucrats, corporate executives, and union leaders had forged an undemocratic alliance. The worst members of the power elite, Mills believed, were union leaders who had betrayed their communist or “Old Left” allies. Labor leaders, however, were only part of the problem. In Mills’s view, the white working class was racist and imperialist. It was up to intellectuals, chiefly faculty and students, to become the vanguard of a “New Left.” Radicalized college graduates would become the teachers, journalists, and bureaucrats who would destroy the Power Elite from within.

Where Mills dissected post-World War II power relations, Williams transformed the historical study of American foreign policy. To Williams, the United States had always been an expansionist nation. It was irrelevant which political party executed American foreign policy, because both Republicans and Democrats promoted a “liberal capitalist State.” Williams concluded the United States could not end injustice at home until it had dismantled its empire abroad.

Unlike Williams and Mills, Marcuse was a refugee from Nazi Germany with first-hand exposure to totalitarian rule. The lessons Marcuse drew from that experience shaped his view of the United States, which he came to regard as only marginally different from Nazi Germany. Marcuse believed democracy was a disguise that hid America’s true dictatorial nature. When civil libertarians called for all points of view to be heard, they were really promoting what Marcuse called “oppressive tolerance.” Free speech allowed racism and imperialism to flourish, he asserted. The pursuit of social justice required intellectuals to shut down their ideological opponents, whether by verbally disrupting their talks or by resorting to violence.

The rise and evolution of the 1960s New Left owed much to Mills, Williams, and Marcuse. In 1962, the recently formed Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) met at Port Huron, Michigan. Fifty-nine delegates, mostly students from such elite universities as Brandeis, Harvard, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Yale, drafted a manifesto, “The Port Huron Statement.” SDS became the focus of campus anti-war protest, even though other peace groups arose, including the Student Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (SMC).

The SDS helped promote protests against the Vietnam War and “predatory” capitalism. This picture shows students at University of Michigan protesting against the Dow Chemical company in 1969. (credit: “March against Dow; MD_70029_002,” by Jay Cassidy, Jay Cassidy photographs, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan).

Drawing inspiration from Mills and Williams, Tom Hayden, the principle author of the “Port Huron Statement,” proclaimed that “exaggerated and conservative anticommunism seriously weaken democratic movements and spawn movements contrary to the interests of basic freedoms and peace.” Although Marcuse’s works were not explicitly cited at the 1962 SDS meeting, there were members who acted in his spirit. Al Haber, the first SDS president, had argued a year earlier that student activists should not tolerate their conservative counterparts on campus, because they were “racist, militaristic, imperialist butchers.”

Initially, SDS experienced slow growth. SDSers threw themselves into community civil rights demonstrations, picketing stores that would not serve African Americans. In 1964, a few hundred white college students, some of them SDSers, went to Mississippi to participate in a voter registration drive known as “Freedom Summer.” Southern law enforcement responded with violence, most famously assisting in the execution of three civil rights volunteers in Philadelphia, Mississippi.

Freedom Summer galvanized its participants. White students who returned from the South took part in large-scale demonstrations, most notably the 1964 Berkeley Free Speech Movement. Meanwhile, many African American students came away from their experiences convinced they must separate themselves from whites if they were to control their destinies. In 1966, SNCC, the largest black student civil rights organization, expelled its white members.

Democratic president Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War in 1965 gave SDS a cause of its own, as well as a recruiting boost. SDS leaders opposed the war because they felt it was unjust and feared being drafted. As the war continued to escalate, so did the militancy of anti-war students.

College campuses became centers of anti-war protest for several reasons. First, the United States had recently welcomed the largest birth cohort in its history; 76 million people were born during the baby boom from 1946 to 1964. Subsequently, college enrollment swelled, from three million in 1960 to 10 million by 1970. The number of faculty also increased, from 196,000 in 1948 to more than 500,000 20 years later. Most of the student and faculty anti-war activists were clustered in the liberal arts.

Second, along with the enrollment growth of universities, many colleges engaged in military-related research or allowed recruiters from corporations with military contracts to come to campus in search of new employees. Recruiters from Dow Chemical and General Electric (GE), among others, became targets of student and faculty protesters. Dow aroused anti-war ire because it manufactured napalm, a chemical weapon used in Vietnam; GE made military aviation equipment. By 1967, corporate recruiters were not just being heckled; some were assaulted.

This 1969 poster from SMC denounced General Electrics as a war profiteer.

Third, given the size of the baby boom cohort, the Department of Defense could afford to give draft deferments to millions of male students. Because just 17 percent of college students came from working- and lower-middle-class families, it was no surprise that 80 percent of the youths who served in the military came from blue-collar backgrounds. Although students could avoid the Vietnam War by remaining in college until they were too old to be drafted, there was always the danger they would flunk out and then be drafted. Fear of the draft fed the ranks of anti-war protestors.

By 1968, SDS had grown to 100,000 members. Student anti-war protestors had a common demographic profile. Most came from middle- to upper-middle-class families and grew up in post-World War II suburbs, where there were few working-class whites or racial minorities. Some claimed elite backgrounds. SDS leader Rennie Davis, who helped organize the disruption of the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, was the son of one of President Truman’s foreign policy architects. Craig McNamara, the son of Johnson’s secretary of defense, kept a communist North Vietnamese flag in his Stanford University dorm room and smashed shop windows during anti-war protests.

In the summer of 1968, numerous students and activists violently protested outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Federal troops were sent in to restore order.

Ninety-five percent of anti-war student activists had been brought up in Democratic households. Few Republicans became anti-war activists; Diana Oughton, the daughter of a wealthy Illinois business executive and politician, was a notable exception. A third of SDS members had parents who were part of the 1930s Old Left. Given their ideological upbringing, such New Left activists were given the nickname “red diaper babies.”

If anti-war student activists had working-class backgrounds, they tended to go to less elite state universities; for example, Kent State as opposed to Michigan. They were often leery of engaging in violent protests and argued that police officers and soldiers carried loaded guns, which they would use if they felt threatened. Students from more affluent backgrounds were often dismissive of such warnings because they often had less familiarity with the police or military.

By 1969, the campus anti-war movement began to collapse. Republican President Richard Nixon suspected that most students protested the Vietnam War because they feared being drafted. He ended the student deferment and established a draft lottery. Because Nixon was then withdrawing U.S. troops from South Vietnam, the higher a young man’s draft number, the less likely he would be inducted. Nearly all campus anti-war protest ended. Although Nixon’s April 1970 invasion of Cambodia triggered renewed student unrest and led to the killing of four students at Kent State by the Ohio National Guard, once it became obvious that he was not calling up more troops, the demonstrations ended.

Campus anti-war protest also faded away in 1969 after SDS splintered. One SDS faction, known as Progressive Labor (PL), followed the teachings of Chinese communist leader Mao Tse-Tung. SDS-PL recognized that a minority movement of privileged intellectuals was doomed and therefore went into factories to recruit white workers. Its efforts failed, vindicating Mills’s contention that working-class whites were too culturally conservative to become revolutionaries.

Another SDS faction became known as the Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM). RYM took its inspiration from a 1965 Bob Dylan song, “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” which had an enigmatic line: “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” The SDS-RYM faction embraced the name “Weathermen.” The Weathermen hoped to launch a guerrilla insurgency in the United States. As they chanted, “Bring the war home!”, they attempted to assassinate police officers and soldiers, rob armored cars and banks, burn campus Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) buildings, and plant bombs in corporate offices.

The Weathermen failed at nearly everything they attempted. In 1970, three members died while constructing a bomb they had planned to detonate at a military installation. Diana Oughton was among the dead, as was Terry Robbins, who had helped organize the Weathermen at Kent State. Most of the Weathermen went underground, eluding the FBI for years until they resurfaced. Few served any jail time.

Review Questions

1. Which New Left document did Columbia University sociologist C. Wright Mills inspire?

- The Power Elite Statement

- The Port Huron Statement

- The Sharon Statement

- The Kent State Statement

2. The New Left believed which group was the vanguard of radical social and economic change?

- The white working class

- The power elite

- Intellectuals

- The Republican Party

3. Most anti-war student activists of the 1960s came from

- rural Republican households

- working-class households

- urban, politically independent households

- Democratic households

4. The aftermath of the Freedom Summer led to

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s dominance of the civil rights movement

- calls for greater militancy in civil rights organizations

- rejection of the Berkeley free speech movement

- financial collapse of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

5. The New Left argued that

- labor unions had abandoned the old left’s goals by joining the power elite

- current American foreign policy goals in Southeast Asia were attainable

- the United States served as a model of racial tolerance and moderate foreign policy

- the white working class would be the central core of the New Left’s power

6. According to the New Left, the power elites were

- college professors and students

- former federal bureaucrats, union leaders, and corporate executives

- suburban voters

- the urban working class

7. College campuses became centers of anti-war protest for all the following reasons except

- increased college enrollment by members of the baby boom generation

- military and industrial recruitment on college campuses

- military deferments for college attendance

- high numbers of college graduates among enlisted soldiers’ ranks

8. Anti-war protests increased during the Vietnam War with the

- institution of the draft

- passage of Great Society legislation

- spread of Jim Crow legislation

- presidential election of Richard Nixon

Free Response Questions

- Compare the demographics of the baby boomers who protested the Vietnam War with those who fought in the war.

- Discuss the New Left’s critique of American society and foreign policy.

AP Practice Questions

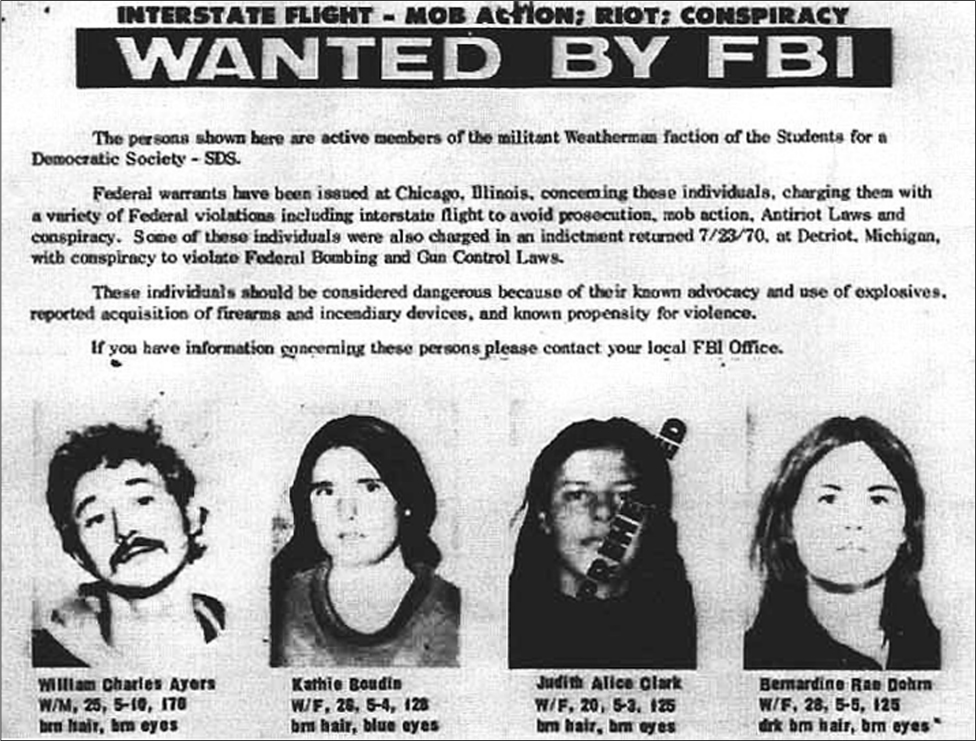

A 1970 FBI Wanted poster.

1. The event that most likely shaped the situation described in the poster was the

- failure of the New Deal

- Civil Rights Act of 1964

- Vietnam War

- feminist support for the Equal Rights Amendment

2. The message of the poster most directly illustrates

- debates over civil rights strategy and tactics

- the fringes of the counterculture

- support for Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society

- advocacy for changes in sexual norms

3. Which of the following best describes a political effect of the situation alluded to in the poster?

- a resurgent conservatism movement

- an expansion of the policy of containment

- passage of voting rights acts

- an end to social justice movements

Primary Sources

Marcuse, Herbert. “Repressive Tolerance.” 1965. http://www.marcuse.org/herbert/pubs/60spubs/65repressivetolerance.htm

Mills, C. Wright. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press, 1959.

Port Huron Statement draft. 1962. http://www.sds-1960s.org/PortHuronStatement-draft.htm

Williams, William A. The Tragedy of American Diplomacy. New York: Delta Publishing Co., 1962.

Suggested Resources

DeBenedetti, Charles. An American Ordeal: The Antiwar Movement of the Vietnam Era. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1990.

Gitlin, Todd. The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage. New York: Bantam, 1993.

Heineman, Kenneth J. Campus Wars: The Peace Movement at American State Universities in the Vietnam Era. New York: New York University Press, 1993.

Heineman, Kenneth J. Put Your Bodies Upon the Wheels: Student Revolt in the 1960s. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001.

Isserman, Maurice, and Kazin, Michael. America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Klatch, Rebecca E. A Generation Divided: The New Left, the New Right, and the 1960s. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999.

Lyons, Paul. The People of this Generation: The Rise and Fall of the New Left in Philadelphia. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003.

Miller, James. “Democracy is in the Streets”: From Port Huron to the Siege of Chicago. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994.

Schneider, Gregory L. Cadres for Conservatism: Young Americans for Freedom and the Rise of the Contemporary Right. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Wells, Tom. The War Within: America’s Battle Over Vietnam. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.