Essay: The Constitution

When the American Founders declared independence from Britain, they explained that they were doing so because its government was violating their inalienable rights, which include “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” As they organized to fight the British and write the Declaration of Independence, the American colonists formed a confederation of states with some basic agreements called “The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union.” The Articles of Confederation enabled them to cooperate in waging the Revolutionary War and to speak with a single voice when negotiating for weapons and trade with countries like France.

Soon after the war ended, however, many Founders began to argue that the Articles of Confederation were not adequate to secure the rights they had fought to defend. Any law or treaty established under the Articles could be ignored by a state government. Citizens of one state could be treated with unfairly negative bias by courts in another state. States were beginning to tax one another’s products, threatening to undermine American prosperity by hampering free trade.

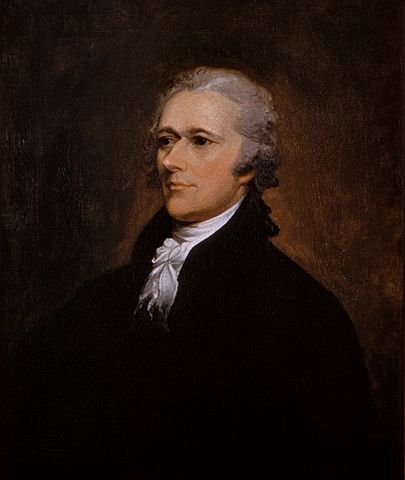

“The peace of the whole,” argued Alexander Hamilton, “ought not to be left at the disposal of a part” (Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 80, 1788).

Americans had battled one of the most powerful nations on earth because its king trampled their rights. Now many believed they faced the opposite problem: a government without enough authority to pay its debts, guarantee equal treatment before the law, or fund a small defensive army.

As states sent delegates to a convention organized to revise the Articles of Confederation, many ideas emerged about how a national government should work. Despite their differences, most delegates agreed that government should be constrained from abusing citizens’ rights while also possessing sufficient power to protect those rights. They also understood that whatever they proposed needed approval from legislatures in most of the states, which meant that they also had to take into account local interests and concerns.

Their goal—as they eventually explained in the opening sentences (the Preamble) of the Constitution—was “to form a more perfect union.” Many who think the word “perfect” can only mean “flawless” miss what the Constitution’s framers intended. They weren’t claiming that the Constitution would make for a flawless national government. They were using the definition of “perfect” that meant—especially in their day—“complete” or “lacking in no essential detail.” In other words, they desired a true union of states, with enough authority to bind them and their citizens, yet with a universal set of rights and freedom for people to make most governmental decisions in their states and communities.

The Constitution’s preamble also reveals that its framers believed the system they devised—by dividing government into branches that would check one another’s exercise of power, and listing specific government powers in order to ensure rulers wouldn’t imagine they had more authority than intended—would “establish justice” for its citizens.

Justice meant that citizens would be treated equally and fairly by their government and also have their persons and property protected.

This more perfect union, rooted in ideas of freedom, individual responsibility, and justice, would help to “insure domestic tranquility” between states and their citizens and also provide “for the common defense.” Our national government would have courts to handle disputes between states or between citizens of different states, as well as the power to raise an army if foreign enemies threatened our lands or people.

“Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States,” painting by Howard Chandler Christy

Instead of a mere collection of states as a “firm league of friendship,” the ratification of the Constitution by state conventions would recast the nation as a sovereign entity authorized by “We, the people of the United States.” It would have a government with specific and limited authority. Its leaders would be expected to “promote the general welfare,” meaning they would only pass laws that benefited the nation as a whole and not merely narrow or local interests.

This new, federal government would not make most decisions or take responsibility for making people’s lives better. That would remain the responsibility of individuals and families acting independently or joined together in their communities. That is why the Founders placed such a strong emphasis on virtue. They knew that no government could ever establish peace and prosperity without citizens who were willing to work hard, take care of their families, and stand up for freedom and justice. The job of the federal government would be to protect the freedoms people needed to govern themselves, pursue religion as they saw fit, engage in commerce, and live peaceably alongside one another.

It was designed to “ensure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity.”

United States Constitution

Although delegates disagreed on many points (for example, how to balance the power between the large and small states), they produced a document that they believed gave their proposed national government the necessary power to protect freedom while shackling it with the necessary restrictions to keep it from becoming a tyranny. John Adams wrote John Jay from his diplomatic assignment in Europe:

“A result of accommodation and compromise cannot be supposed perfectly to coincide with everyone’s idea of perfection…But, as all the great principles necessary to order, liberty, and safety are respected in it, and provision is made for corrections and amendments as they may be found necessary, I confess I hope to hear of its adoption by all the states” (John Adams to John Jay, December 16, 1787).