The Election of 1968

Written by: The Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the causes and effects of the Vietnam War

- Explain how and why opposition to existing policies and values developed and changed over the course of the 20th century

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Lyndon B. Johnson’s Decision Not to Run in 1968 Decision Point after discussion of the Vietnam War and its unpopularity to discuss how it affected the presidential election in 1968.

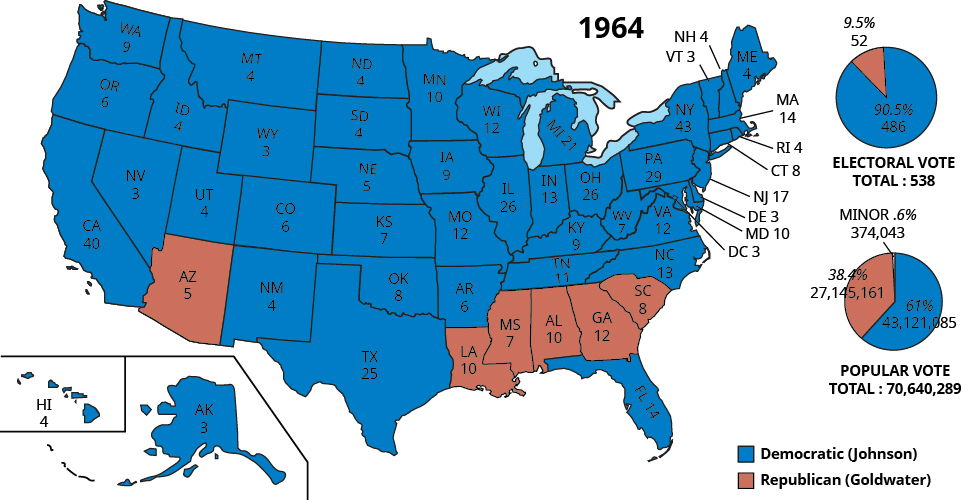

Post-war liberalism reached its zenith with the enactment of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, which followed his massive 1964 electoral win over conservative Barry Goldwater. Some political pundits were even predicting the demise of the Republican Party in national politics. By 1968, however, the unpopular war in Vietnam, social unrest, and a teetering economy had fractured the postwar liberal consensus and New Deal coalition. The growing conservative movement and Republican Party began to emerge as a new majority.

In 1964, Johnson had beaten Goldwater by an astounding 16 percent margin in the popular vote and won 486 electoral votes, as well as overwhelming majorities in both houses of Congress. Johnson saw this as a mandate to push Congress to pass John F. Kennedy’s legislative agenda and complete the legacy of the New Deal. Despite the Great Society, an initially popular Vietnam War, and a booming economy, however, cracks soon began to appear.

This map shows the landslide victory that Johnson won over Goldwater in the presidential election of 1964. (credit: “1964 U.S. Electoral Map” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr, CC BY 4.0)

The Vietnam War became increasingly unpopular as American casualties mounted in the first “television war. “Inflation” tripled to 4.8 percent, and high-paying factory jobs began going overseas. Many working and middle-class Americans were troubled that welfare rolls had tripled. Urban race riots had erupted every summer since 1965, and young African Americans joined the Black Power movement. Violent crime and homicide rates doubled during the decade, and urban dwellers of all races felt unsafe. Against this backdrop, many were angry that the Supreme Court decided in favor of the rights of the accused in cases such as Miranda v. Arizona (1966). Anti-war protestors marched in the streets, and radical students took over university buildings.

On November 30, 1967, Minnesota’s Democratic Senator Eugene McCarthy announced his candidacy for the presidency, challenging the incumbent for the party’s nomination. He represented the progressive wing of the party and focused his campaign on his opposition to the Vietnam War. This issue was of great concern to the young, including anti-war campaign workers who got “clean for Gene” by shaving their counterculture beards.

The war took a fundamental turn on January 31, 1968, when the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong launched surprise attacks throughout South Vietnam. They were attempting to win a military victory that would lead to a general uprising in the south and deliver a psychological blow to the American people, inducing policy makers to give up the war. The uprising never happened, and the North Vietnamese suffered a major tactical defeat but won a major propaganda victory. Americans turned against the war, perceiving a “credibility gap” between Johnson’s promise of impending victory and the reality of the conflict, especially when they saw images of Viet Cong commandos storming the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. News anchor Walter Cronkite publicly broadcast his opposition to the war on the evening news.

On March 10, newspapers reported the stunning news that General William Westmoreland was asking the Pentagon for 206,000 more troops in Vietnam. The story belied the administration’s earlier statements that the United States was making progress in winning the war. As a result, McCarthy almost beat President Johnson in the New Hampshire Democratic primary two days later. Observers were surprised by Johnson’s poor showing in the primary as an incumbent.

On March 16, Senator Robert F. Kennedy, former attorney general and brother of the slain president, entered the race, announcing his candidacy for the Democratic nomination in the Old Senate Office Building where John Kennedy had begun his 1960 campaign. In his speech, Robert Kennedy was also critical of the Vietnam War and pledged to restore “law and order” to American society. He and Johnson disliked each other intensely, and the announcement exacerbated tensions between the two.

Robert F. Kennedy decided to challenge President Johnson in the 1968 primaries for the Democratic candidacy.

Johnson felt beleaguered by the political challenges within his party and the bad news coming out of Vietnam. In late March, he met with several high-ranking foreign policy experts and decided against further escalation of the war. On March 31, the president broadcast a prime-time speech on television. He pledged to implement a partial bombing halt and to initiate peace talks with the North Vietnamese. Johnson then informed his audience, “I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for President.”

As the country was processing this surprising news, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated outside a motel while supporting a strike by black sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. The shooting of the civil rights leader and frustrations with the pace of civil rights and anti-poverty programs triggered race riots in more than 130 cities across the country, resulting in 46 deaths, 20,000 arrests, and more than $100 million in damage.

Only a little more than a month before, the Kerner Commission had delivered a controversial report on persistent urban riots. It concluded that white racism was responsible for the riots and that the federal government should spend billions of dollars to alleviate poverty for blacks in cities. With the Great Society in retreat, and with many Americans opposed to what they considered a call to reward the rioting, Johnson ignored the Commission’s proposal. The riots over King’s death demonstrated that a solution to the seemingly intractable problem of race relations was not to be found any time soon.

Former Alabama governor George Wallace, who had entered the race as a third-party candidate for the American Independent Party only a few days before King was killed, stood to benefit the most from the violent aftermath. Wallace appealed to many southern whites and northern blue-collar ethnics who questioned black equality, were concerned about the increase in crime and rioting, thought the Great Society welfare programs rewarded people who cheated the system, and wanted to restore what Wallace argued were traditional values. His populist appeal was sprinkled with one-liners and resonated with American voters who were resentful of elites and troubled about the state of society.

Former Alabama governor George Wallace ran as a third-party candidate for president in 1968 on a platform of law and order and a rejection of racial integration.

Many Americans were aghast at the unrest on college campuses. Campuses were hot spots of anti-war sentiment as students demonstrated against university ties to the government and military, marched against the war, and protested by shutting down classes or occupying buildings. In late April, students at Columbia University occupied buildings to protest a new gym because they thought it segregated black members of the adjacent Harlem community and took public land. They also used the protest to express larger social grievances. After some equivocation by the administration, the police forcibly expelled the students, leading to hundreds of arrests and injuries to students and police.

In the middle of these chaotic events, Vice President Hubert Humphrey announced his candidacy for the Democratic nomination. Humphrey was a liberal former senator from Minnesota who was aligned closely with labor unions and the Democratic establishment. His candidacy was burdened by the failures and unpopularity of the Johnson administration, especially when the president refused to allow him to take independent stances on issues that Johnson perceived as critical.

Meanwhile, Robert Kennedy, Humphrey’s Democratic rival, used the mystique around the “Camelot” image of his brother’s presidency to draw increasingly large audiences throughout the spring. He appealed to young people and spoke frequently of the disadvantaged in American society. Although his speeches drew wildly enthusiastic crowds, he had difficulty translating his popularity into primary votes. On June 4, however, he won the California primary and had just concluded a late-night victory speech when he was gunned down by Sirhan, a young Arab nationalist, while exiting through the hotel kitchen.

The campaigns continued through the summer months, leading up to the two parties’ national nominating conventions. McCarthy’s campaign lost steam in the wake of Robert Kennedy’s assassination, and Humphrey emerged as the front runner. Likewise, Republican candidate Richard Nixon fended off challenges from California governor Ronald Reagan, representing the conservative wing of the Republican Party, and New York governor Nelson Rockefeller, representing its liberal wing.

The Republicans held their national convention in Miami and easily nominated Nixon as their presidential candidate. In his acceptance speech, Nixon addressed the frustrating challenges confronting the country. “When the strongest nation in the world can be tied down for four years in Vietnam with no end in sight, when the richest nation in the world can’t manage its own economy, when the nation with the greatest tradition of the rule of law is plagued by unprecedented racial violence – then it’s time for new leadership for the United States of America.” He appealed to those who became known as the “silent majority” of Americans, but he also made the unfortunate choice for vice president of Maryland governor Spiro Agnew, who later resigned and was jailed for accepting bribes.

Later that month, the Democrats held their convention in Chicago. The delegates were divided over whether to criticize the sitting Democratic president and over the future course of the party. South Dakota’s Senator George McGovern chaired a committee that expanded representation of minorities and progressives at Democratic conventions and reduced that of party regulars. This shifted the party to the left for several years.

Most significantly, thousands of young anti-war protestors and anarchist Yippies (who made a mockery of establishment politics) descended on Chicago to confront the authorities and the Democrats. Mayor Richard Daley mobilized 12,000 officers and 6,000 National Guard troops around the city to keep order. A disaster resulted. Violent demonstrations occurred in Lincoln Park and then outside the convention. The police and protestors clashed before 89 million television viewers, who were shocked by the violence. Most polls showed that Americans blamed the incident on the protestors.

The National Guard keeping order outside the Democratic National Convention in 1968.

During the final months of the election season, Nixon appealed to voters with what he called a secret plan to end the Vietnam War, though he was purposefully vague about the details and continued to appeal to law and order. The backbone of his campaign was his “southern strategy” of pro-business policy, low taxes, a strong national defense, opposition to forced busing for racial integration, and support for traditional values. Humphrey had difficulty distancing himself from Johnson and ran a fairly lackluster campaign. Wallace continued to draw off Democratic support from Humphrey but blundered in selecting Air Force general Curtis LeMay as his vice presidential candidate. LeMay promised to bomb North Vietnam “back into the Stone Age” and use nuclear weapons. This threat of a dramatic escalation of the war further tarnished Wallace’s image.

On October 31, President Johnson announced at the last minute that the United States would stop bombing North Vietnam and engage in peace talks. South Vietnam president Nguyen Van Thieu rejected the proposal. Johnson had had the South Vietnamese embassy in Washington wiretapped, which may have revealed that Nixon had indirectly helped foil the peace proposal.

On Election Day, Nixon won the presidency by a relatively narrow vote, taking 301 electoral votes to Humphrey’s 191 and Wallace’s 46. Nixon and Wallace split the Sun Belt, and Humphrey won large industrial states in the Rust Belt of the Northeast and Midwest in addition to Texas. Over the ensuing decades, the Republicans came to dominate national politics on the strength of winning the formerly Democratic Solid South, making inroads into the northern ethnic vote, and bolstering a growing conservative movement. The Democrats shifted to the left after the New Deal coalition largely collapsed in the transformative 1968 election.

Review Questions

1. During the presidential campaign of 1968, the Democratic Party

- nominated Robert F. Kennedy to be its standard bearer before his assassination

- found itself split between factions supporting and opposing the war

- emphasized it was running a “law and order” campaign

- expelled George Wallace for his segregationist views

2. In the 1968 presidential election, the Democratic party lost support in

- the South or “Sun Belt”

- the Northeast

- the “Rust Belt” in the Midwest

- Texas

3. President Lyndon B. Johnson responded to the events of 1968 by

- announcing his candidacy for the upcoming fall presidential election

- calling on North Vietnam to formally begin peace negotiations

- escalating bombing raids on North Vietnam

- endorsing the campaign of Richard Nixon

4. Richard Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign appealed to those voters

- seeking law and order to counter urban and social unrest

- looking to expand the policy of containment

- supporting groups such as the Students for a Democratic Society and the Black Panthers

- advocating expansion of the welfare state

5. Robert F. Kennedy’s announcement that he would enter the race for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1968

- signaled the resurgence of public opinion in favor of the Vietnam War

- represented a serious challenge to Lyndon B. Johnson’s renomination

- ensured a Republican presidential victory

- supported a similar political agenda as that of Governor George Wallace of Alabama

6. The events of 1968 led President Lyndon B. Johnson to alter his foreign policy by

- escalating the presence of ground troops in Vietnam

- dramatically increasing bombing of Laos and Cambodia

- promoting peace talks with North Vietnam

- expanding the policy of containment in Southeast Asia

Free Response Questions

- Explain how the events of 1968 contributed to the backlash phenomena that helped elect Richard Nixon.

AP Practice Questions

“With American sons in the fields far away, with America’s future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office the Presidency of your country.

Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President. But let men everywhere know, however, that a strong and a confident and a vigilant America stands ready tonight to seek an honorable peace; and stands ready tonight to defend an honored cause, whatever the price, whatever the burden, whatever the sacrifice that duty may require.”

President Lyndon Baines Johnson, “On Vietnam and Not Seeking Reelection,” March 31, 1968

Refer to the excerpt provided.1. The text in the excerpt most directly led to

- the end of the Cold War

- the rise of the limited welfare state

- a scramble for leadership within the Democratic Party

- the passage of Great Society legislation

2. The excerpt most directly reflected a growing belief that

- postwar collective security agreements needed to be expanded

- postwar decolonization did not pose a threat to American national interests

- the policy of containment had its limitations

- the counterculture represented the views of the 1950s

3. The text in the excerpt was written in response to

- the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union

- military actions undertaken in Southeast Asia

- nationalist movements in Africa and the Middle East

- tensions between Communist China and Taiwan

Primary Sources

Johnson, Lyndon B. “A New Step Toward Peace.” March 31, 1968.The Department of State Bulletin, 58, no. 1503 (1968):481-86.

Suggested Resources

Brands, H.W. Reagan: The Life. New York: Doubleday, 2015.

Carter, Dan T. The Politics of Rage: George Wallace, the Origins of the New Conservatism, and the Transformation of American Politics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995.

Clifford, Clark. Counsel to the President: A Memoir. New York: Random House, 1991.

Cohen, Michael A. American Maelstrom: The 1968 Election and the Politics of Division. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Farrell, John A. Richard Nixon: The Life. New York: Doubleday, 2017.

Gilbert, Marc J., and William Head, eds. The Tet Offensive. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1996.

Goudsouzian, Aram. The Men and the Moment: The Election of 1968 and the Rise of Partisan Politics in America. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Gould, Lewis L. 1968: The Election that Changed America. New York: Ivan R. Dee, 1993.

Hayward, Steven F. The Age of Reagan: The Fall of the Old Liberal Order, 1964-1980. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2001.

Herring, George C. America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975. Fourth revised ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2002.

LaFeber, Walter. The Deadly Bet: LBJ, Vietnam, and the 1968 Election. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005.

Nelson, Michael. Resilient America: Electing Nixon in 1968, Channeling Dissent, and Dividing Government. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2017.

Offner, Arnold A. Hubert Humphrey: The Conscience of the Country. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

Patterson, James T. Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Sandbrook, Dominic. Eugene McCarthy: The Rise and Fall of Postwar American Liberalism. New York: Knopf, 2004.

Schmitz, David. The Tet Offensive: Politics, War, and Public Opinion. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2005.

Spector, Ronald H. After Tet: The Bloodiest Year in Vietnam. New York: Vintage, 1993.

Young, Marilyn B. The Vietnam Wars, 1945-1990. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.