The Great Awakening

Written by: Thomas Kidd, Baylor University

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain how and why the different goals and interests of European leaders and colonists affected how they viewed themselves and their relationship with Britain

Suggested Sequencing

Before reading this Narrative, students should be familiar with the role of religion and challenges to religious authority in the New England colonies (Anne Hutchinson and Religious Dissent and The Salem Witch Trials Narratives). This Narrative should be followed by the What Was the Great Awakening? Point-Counterpoint.

During a cool October 1740 morning in Kensington, Connecticut, Nathan Cole was hard at work in his field, as he had been since sunrise. Suddenly his labor was interrupted by a passing messenger’s shouts: at 10 o’clock the evangelist George Whitefield was going to preach in nearby Middletown. Nathan immediately dropped his tools in the field, ran to fetch his wife, and saddled his horse. He and his wife joined a throng of others hurrying along the roads to Middletown, afraid they would arrive too late to hear the famous preacher.

After receiving his degree from Oxford University, Whitefield had begun a life of itinerant preaching and evangelism. Rather than expounding on the intricacies of Christian doctrine, he appealed to the emotions of his listeners at home in England, and now, still only twenty-five years old, he had brought his new style to the American colonies. For weeks, Nathan Cole had heard reports that Whitefield’s preaching tour of the colonies was drawing huge crowds numbering in the tens of thousands. Many people in the audience experienced the “new birth” of evangelical conversion. Watching the celebrated preacher begin, Cole began to tremble. “My hearing him preach,” he wrote in his diary, “gave me a heart wound.”

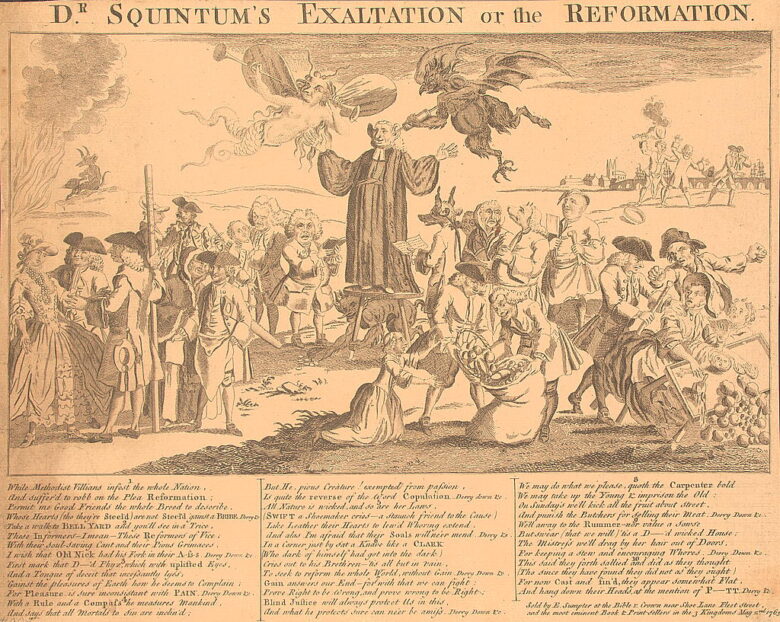

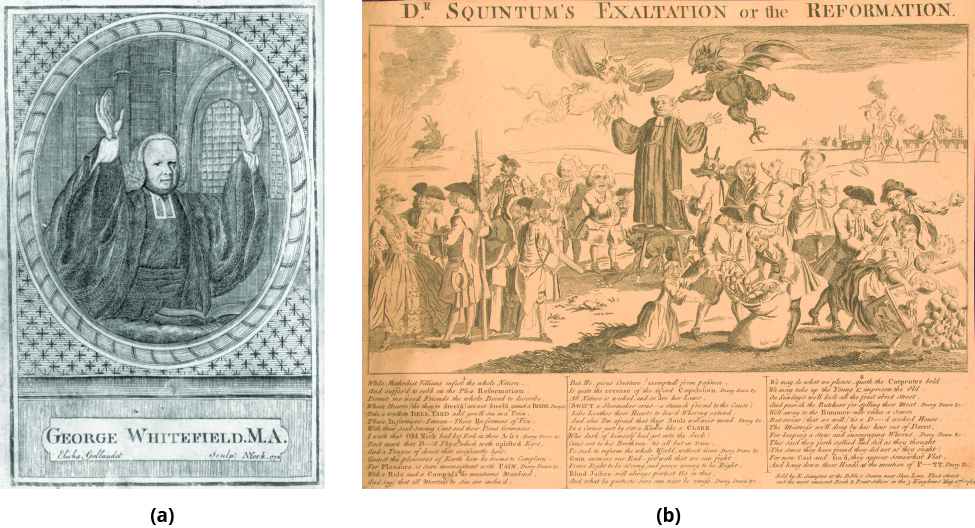

Compare the two images of George Whitefield: (a) a 1774 portrait by engraver Elisha Gallaudet and (b) a 1763 British political cartoon entitled “Dr. Squintum’s Exaltation or the Reformation.” Dr. Squintum was a nickname for Whitefield, who was cross-eyed. What details can you find each in image that indicate the artists’ respective views of the preacher?

Whitefield’s message was simple: It was not enough to be baptized or go to church. Each individual must be converted by the Holy Spirit of God through a personal, wrenching examination of his or her own corruption and sinfulness. The youthful, twenty-five-year-old English minister held the crowd at Middletown spellbound with his masterful, emotional pleas that each person receive God’s gift of salvation and be “born again.” Countless listeners, including Nathan Cole, were converted.

Whitefield was not America’s first revival preacher. Just a few years earlier, Jonathan Edwards, a minister in Northampton, Massachusetts, had led a series of awakenings too. Possibly the greatest theologian the colonies had ever produced, Edwards was a master of rhetoric who preached on human sinfulness and the need for divine grace. Most famously, he delivered a 1741 sermon titled Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. Under Edwards’ preaching, a town-wide revival broke out in Northampton from 1734 to 1735. In London, Edwards published a compelling account of this revival, A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God. As George Whitefield, England’s John Wesley, and other evangelical ministers read Edwards’ narrative, they realized they were part of a series of religious revivals that began in the colonies and spanned the Atlantic. They were in the middle of what historians came to call “The Great Awakening.”

This image shows the frontispiece of Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God, A Sermon Preached at Enfield, July 8, 1741,by Jonathan Edwards. Edwards was an evangelical preacher who led a Protestant revival in New England. This was his most famous sermon, the text of which was reprinted often and distributed widely.

Over the course of his seven preaching tours of the colonies, Whitefield reached 75 to 80 percent of the population, sometimes addressing crowds that approached thirty thousand listeners. His revivals were controversial. Local ministers resented Whitefield and other traveling preachers coming to their towns uninvited. When revivalists drew massive crowds and preached in public, local ministers and churches worried the preachers were undermining their spiritual authority. Worse, some evangelical preachers, such as New Jersey’s Gilbert Tennent, dared to suggest that many of the established church’s pastors were not converted. Tennent charged that some pastors were Christians only in name, because they had not yet experienced the “new birth.” He called true believers to leave the lukewarm established congregations and join new, “pure” churches.

In addition to challenging religious authorities, the revivals could also challenge social conventions. Following their conviction that all believers were equal before God, some evangelicals allowed women to “exhort,” or preach informally, during meetings. In Ipswich, Massachusetts, a gathering of evangelicals in 1742 was amazed when a “spirit of prophecy” filled a female convert named Lucy Smith. Smith preached the Gospel to this assembly for over two hours. White evangelicals even ordained converted African Americans and American Indians to preach or be missionaries, although typically only to their own communities. Some evangelicals began to argue that, in light of the Gospel’s implications, slave owning was sinful. These egalitarian impulses were unprecedented in colonial society and challenged racial and social hierarchies, especially in the South.

Evangelical teaching also challenged barriers based on social class. Uneducated, poor whites with no theological training often felt a strong calling to preach. Their sermons were frequently highly charged, even frenzied, displays of emotion and, according to some critics, resulted in indecent and immoral behavior. However, the messages of these radical preachers resonated with those lower on the social ladder. Common people and American Indians loved the emotional, radical preaching of James Davenport, a college-educated preacher in New England. In 1743, in New London, Connecticut, Davenport and his followers built a bonfire and instructed the audience to throw their religious books into it. Davenport then turned his eye to their fancy clothing (“cambric caps, red-heeled sho[e]s, fans, necklaces, gloves”), all of which deserved to be burned. Davenport led by example, pulling off his own pants and throwing them on the fire. But this action went too far for some audience members. A woman snatched his clothes off the flames and threw them in his face, and his audience rebuked him.

Many critics thought the emotional appeal of the “New Light” evangelical ministers was foolish and led to social chaos. The New Light ministers rejected the rationalism of the Enlightenment and appealed to the passions of the audience members rather than their reason, which resulted in emotional reaction and immediate conversion. The main source of opposition was conservative pastors of the established churches, particularly Anglicans and Congregationalists. These “Old Light” ministers insisted upon sober and rational sermons and religious practices and rejected the passionate New Light theology and style of the evangelical preachers. The Old Light ministers successfully banned the New Light ministers from preaching in several churches and towns.

By the late 1740s, the New England revivals had cooled, but the Great Awakening’s effects were widespread and long-lasting as the fervor continued to spread to the southern colonies in the ensuing decades. The revivals had weakened the hold of the established churches in colonial America, and large numbers of Christians joined new evangelical churches like those of the Baptists or Methodists.

The Great Awakening also contributed to colonial religious liberty by changing the balance of religious power. During the American Revolution and the struggle for individual liberty, Baptists used their new numbers and influence to challenge religious establishments, first in Virginia and then throughout the new nation. Many evangelicals called for an end to government-supported denominations, which received tax money and lands called “glebes” to support ministers and churches. After the Revolution, opposition to established churches helped inspire the First Amendment’s prohibition of the “establishment of religion” and its guarantee of “free exercise” of religion. The founders believed that freedom of conscience was an inalienable right of all individuals. The religious landscape of the new nation was never the same.

The Great Awakening helped prepare the colonies for the American Revolution. Its ethos strengthened the appeal of the ideals of liberty, and its ministers and the members of the new evangelical faiths strongly supported the Revolution. The drive for religious liberty against a tyrannical religious authority fed into the movement for civil liberty against the unjust political authority of the British in the 1770s. Likewise, the evangelical teaching that each individual believer was equal before God made it easier for people to accept the radical implications of democracy and to question authority. Thus, the same movement that sent Nathan Cole sprinting out of his field that October morning helped set the stage for American independence. The Great Awakening was the most significant religious and cultural upheaval in colonial American history, and helped forge U.S. civil and religious liberties emerging in the mid-eighteenth century.

Review Questions

1. Many historians believe the Great Awakening helped set the stage for the American Revolution. Which of these ideas best supports that argument?

- Evangelical teaching during the Great Awakening proposed that each individual believer was equal before God, which made it easier to accept the radical implications of democracy.

- Many Great Awakening preachers were political radicals.

- Churches under the Great Awakening were much more democratic than earlier churches had been.

- Great Awakening theology argued that only those who were among God’s “elect” would go to Heaven when they died.

2. How did local ministers feel about George Whitefield and other traveling preachers coming to their towns uninvited?

- They welcomed these popular preachers, who brought more people into their church.

- They worried that revivalists undermined their spiritual authority.

- They appreciated the chance to study the techniques of the traveling preachers.

- They were indifferent to the Great Awakening preachers.

3. Which of these was not a way in which the ministry of the Great Awakening challenged social conventions?

- Following their conviction that all believers were equal before God, some evangelicals allowed women to “exhort,” or preach informally during meetings.

- White evangelicals ordained converted African Americans and American Indians to preach or be missionaries

- Some evangelicals began to argue that, in light of the Gospel’s implications, enslaving people was sinful.

- Sometimes children were allowed to preach from the pulpit.

4. Who were the “Old Lights”?

- People who read books from the Enlightenment and did not attend church or meeting on Sundays

- Jewish residents of Newport, Rhode Island

- Elderly people admired for their knowledge of the Bible and scripture

- Ministers and their parishioners who insisted upon sober and rational religious practices and rejected the style of the evangelical preachers

5. Who were the “New Lights”?

- Critics who thought the emotional appeal of the evangelical ministers was foolish and led to social chaos

- Followers of Great Awakening evangelical preachers whose sermons were notable for their emotion and dramatic appeal

- People interested in Enlightenment interpretations of the Bible

- Enlightenment preachers who wanted to introduce their parishioners to concepts such as deism

6. It has been argued that the Great Awakening contributed to a decline in the importance of established religion during the second part of the eighteenth century, because

- people were alienated by the anti-intellectual quality of the sermons they had to listen to

- many ministers simply quit the profession and denounced any form of Christianity

- the revivals had weakened the hold of established churches in colonial America

- many Americans converted to Judaism or Islam

7. George Whitefield was immensely popular as a preacher in the colonies because

- he explained the intricacies of Christian doctrine with great precision and erudition

- he preached to small groups so he could get to know his audience

- he appealed to the emotions of his listeners, many of whom experienced the “new birth” of evangelical conversion

- he made his listeners feel good about themselves and reassured them that they would be admitted to Heaven

8. How did the Great Awakening affect laws in those states that supported an official religion through taxation?

- Members of the “new” religions resented being assessed for a church they did not attend, so they called for an end to the practice.

- The Great Awakening had little effect because members of these new religions took little interest in money, which they regarded as the invention of the Devil

- Members of new churches began demanding that they also be supported in proportion to their population in the colony.

- Baptists were able to get support, but Presbyterians were regarded as too radical and out of the mainstream.

Free Response Questions

- Explain how the Evangelical teaching of the Great Awakening challenged barriers based on social class.

- Explain how the Great Awakening laid some of the groundwork for the American Revolution.

- Explain the connections between the Great Awakening and the first clause of the First Amendment.

AP Practice Questions

“When I saw Mr. Whitefield come upon the Scaffold he looked almost angelical, a young, slim slender youth before some thousands of people with a bold undaunted countenance, and my hearing how God was with him every where as he came along it solumnized my mind, and put me into a trembling fear before he began to preach; for he looked as if he was Cloathed with authority from the Great God, and a sweet solemn solemnity sat upon his brow. And my hearing him preach gave me a heart wound; by Gods blessing my old foundation was broken up, and I saw that my righteousness would not save me; then I was convinced of the doctrine of Election and went right to quarrelling with God about it, because all that I could do would not save me; and he had decreed from Eternity who should be saved and who not.”

Nathan Cole in Connecticut, 1740

Refer to the excerpt provided.1. Which conclusion would a historian not draw from the excerpt provided?

- That Nathan Cole took only a slight interest in hearing George Whitefield

- That Nathan Cole took a tremendous interest in hearing George Whitfield

- That Nathan Cole was a farmer

- That Nathan Cole likely identified as an “New Light”

2. Based on the excerpt provided, how could a historian describe Whitfield’s appeal to his audience?

- Whitefield could not project his voice unaided to thousands of people.

- Whitefield looked a bit sloppy, but his audience overlooked that.

- Whitefield’s effect was almost overpowering.

- Whitefield was not a Calvinist preacher.

Primary Sources

“Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”: http://greatawakeningdocumentary.com/items/show/35

Suggested Resources

Isaac, Rhys. The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790. Chapel Hill: University Press of North Carolina, 1999.

Kidd, Thomas S. George Whitefield: America’s Spiritual Founding Father. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

Kidd, Thomas S. The Great Awakening: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford, 2007.

Kidd, Thomas S. The Great Awakening: The Roots of Evangelical Christianity in Colonial America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Marsden, George M. A Short Life of Jonathan Edwards. Michigan: Eerdmans, 2008.

Marsden, George M. Jonathan Edwards: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.