The Vietnam War: Ia Drang Valley

Written by: Robert McMahon, Ohio State University

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the causes and effects of the Vietnam War

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with The Vietnam War Experience: An Interview with Veteran William Maxwell Barner III Primary Source to highlight the experience of the U.S. military during the Vietnam War.

In the months immediately following his overwhelming triumph in the 1964 presidential election, Lyndon B. Johnson made several crucial and politically fraught decisions that transformed America’s military role in the ongoing war in Vietnam. Johnson and his chief foreign policy advisers recognized that their South Vietnamese allies teetered on the brink of political collapse, that military momentum had shifted to the Viet Cong guerrillas and their patrons in Hanoi, and that American inaction could well hasten a communist victory. On January 5, 1965, Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara and National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy bluntly informed Johnson that “our current policy can lead only to disastrous defeat.”

This map of North Vietnam and South Vietnam highlights the major cities in both countries. Note the location of Da Nang, where U.S. troops first landed in the area during the Vietnam War, and the Ia Drang Valley, the location of the first major battle between U.S. troops and the People’s Army of Vietnam. (credit: “North and South Vietnam” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr, CC BY 4.0)

Fearful that such an outcome would damage America’s international credibility, embolden its communist adversaries in Moscow and Beijing, and derail his ambitious domestic reform program, Johnson ordered a dramatic escalation of the U.S. military commitment. In mid-February, after a few retaliatory air strikes above the 17th parallel (where Vietnam was divided into North and South), he approved a program of sustained aerial bombardment of North Vietnam. The dispatch of U.S. ground forces quickly, and almost inevitably, followed the onset of the air war. Commanding General William C. Westmoreland worried that without combat troops to provide security, American air bases in South Vietnam would remain highly vulnerable to enemy attacks. Consequently, he asked for two battalions of marines to help defend the key air base at Da Nang. On February 26, the president approved that request, and on March 8, approximately 3,500 U.S. troops waded ashore at the beaches of Da Nang. At the end of July, Johnson announced he was immediately dispatching an additional 50,000 U.S. troops to Vietnam, while privately directing that another 50,000 be sent by the end of the year.

U.S. marines arrived at Da Nang, South Vietnam, in March 1965.

For its part, North Vietnam tried to match the U.S. escalation, hoping the infiltration of its own regular forces into South Vietnam would help trigger the collapse of the Saigon regime before the U.S. military buildup could make a decisive difference. In the fall of 1965, the two contending armies clashed openly in South Vietnam’s central highlands.

The fiercest and most consequential of those clashes occurred in the Ia Drang Valley located in the Central Highlands south of Danang. Elements of the highly mobile U.S. 7th Cavalry Division, using helicopters for high-speed mobility, were conducting search-and-destroy missions in the area when they were attacked by three regiments of the Peoples’ Army of Vietnam (PAVN). Their leader, Colonel Nguyen Huu An, wanted to engage U.S. forces to learn their tactics and abilities. The assaults formed part of North Vietnam’s bold effort to drive to the South China Sea; if successful, that effort could have cut South Vietnam in half.

On November 14, 1965, the 7th Cavalry landed at X-Ray landing zone while B-52s bombed the surrounding enemy positions and nearby artillery provided fire support. For the next three days, the two sides engaged in bloody combat at close quarters, punctuated by heavy U.S. artillery, napalm, and B-52 strikes that exacted heavy losses on enemy forces. When the smoke cleared, the United States had lost 305 soldiers and nearly as many were wounded. According to the imperfect U.S. statistical accounting, North Vietnam had lost 3,561 troops.

U.S. soldiers disembarking from helicopters during the 1965 battle of Ia Drang Valley. U.S. forces relied on helicopters during the battle to land reinforcements and supplies and to evacuate the wounded.

Westmoreland was pleased he had checked the enemy’s drive to the sea and was heartened by the better than ten-to-one ratio of North Vietnamese to U.S. troops killed in action. He touted the Ia Drang fighting as “an unprecedented victory.” It seemed to validate his attrition strategy of using overwhelming firepower to produce high enemy body counts rather than taking territory or decisively defeating armies. That strategy was based on the calculation that if the United States could inflict casualties on the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong at a rate faster than the enemy could recruit replacements, then a “crossover point” could be reached and military victory attained. Defense Secretary McNamara drew a more sober lesson. He warned in the wake of the bloodletting at Ia Drang that monthly U.S. casualty numbers were likely to remain alarmingly high and that even more U.S. troops would be required for the United States to prevail militarily.

The North Vietnamese drew their own lessons. Most fundamentally, they recognized that frontal clashes with a much better-armed adversary, enjoying total air superiority, worked to the distinct disadvantage of PAVN and North Vietnamese forces. Accordingly, for the duration of the war, they carefully avoided conventional battles, preferring guerrilla-style, small-unit actions that allowed them to control the rate of casualties. Hanoi’s goal from the beginning of the U.S. troop buildup in mid-1965 was not to defeat the foreigners but to wait them out. “Don’t worry,” North Vietnamese President Ho Chi Minh told his associates. “I’ve been to America. I know Americans. They are an impatient people. They will leave.” If the PAVN and Viet Cong stayed in the contest, the United States would grow weary of a protracted conflict; by inflicting significant casualties on the Americans, they could hasten that process, no matter how great their own losses. “American boys being sent home in body bags will steadily increase,” prophesied North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap. “Their mothers will want to know why. The war will not long survive their questions.”

America’s goals were as foggy as North Vietnam’s were clear cut, and as unrealistic in light of prevailing military, political, and socioeconomic conditions as Hanoi’s proved largely compatible with those very same conditions. The United States not only sought to block a communist victory in the south but to prevent further communist advances in and beyond Southeast Asia, to reassure allies worldwide about U.S. resolve, and to deter Moscow and Beijing from supporting wars of national liberation. The Johnson administration was convinced that those broader goals required that the United States defeat the insurgency and its northern backers, not just hold off a communist victory. Yet, wary of any actions that might provoke direct Chinese or Soviet intervention, the Johnson administration also believed it had to pursue its objective by means of a limited, rather than a total, war.

Therein lay a major inconsistency in American strategy. Simply put, how could the United States, with anything less than a total commitment, defeat so determined a foe as North Vietnam, a nation willing to make unimaginable sacrifices to advance its cause? And how could the United States force Hanoi to cease its support for the insurgency in the south without resorting to more extreme measures, such as the bombing of population centers, the invasion of the north, even the use of nuclear weapons? Yet to resort to extreme measures of that sort would have represented a wholesale repudiation of American values. It would also have been so wildly disproportionate a response to the Vietnam problem that the very allies the United States was seeking to reassure would more likely have been repulsed. Finally, such extreme measures likely would have invited the very countermoves from Beijing that Johnson most feared.

Review Questions

1. President Lyndon B. Johnson authorized a dramatic escalation of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam in 1964 primarily because

- South Vietnam was on the verge of political and military collapse

- the public overwhelmingly rejected the policy of containment

- a close electoral victory had called for dramatic action to win more public support for the president

- China and the Soviet Union had troops amassed on the border, ready to invade South Vietnam

2. Initially, President Johnson increased the American military presence in Vietnam by ordering

- sustained aerial bombing of North Vietnam

- a surge in ground forces

- increased use of naval gun boats

- deployment of short-range nuclear weapons

3. General Westmoreland pursued an “attrition strategy,” meaning that the United States wanted to

- use napalm to defoliate forest hiding areas

- inflict enemy casualties at a faster rate than replacements could be found

- rely on superior air power to demoralize the enemy

- encourage the defection of large numbers of enemy troops

4. After the battles in the Vietnamese central highlands in 1965, the North Vietnamese strategy became

- direct frontal assaults on American and South Vietnamese positions

- increased use of Soviet troops to confront American and South Vietnamese forces

- use of airpower to dominate South Vietnam

- guerilla tactics designed to wait out American support

5. The battle of the Ia Drang Valley

- led North Vietnam to begin withdrawing its troops from South Vietnam

- prevented North Vietnamese forces from driving to the South China Sea

- forced General William C. Westmoreland to abandon his attrition strategy

- triggered a major political upheaval within the South Vietnamese government

6. North Vietnam’s military strategy during the Vietnam War

- aimed to confront U.S. troops with human wave assaults

- sought to defeat U.S. military forces through frontal attacks on troop concentrations

- sought to continue and extend the tactics used during the battle of the Ia Drang Valley

- depended on patience and a belief that time favored the communist side

Free Response Questions

- Explain why President Lyndon Johnson expanded U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

- Assess the lessons drawn from the Ia Drang battle by the United States and the North Vietnamese.

AP Practice Questions

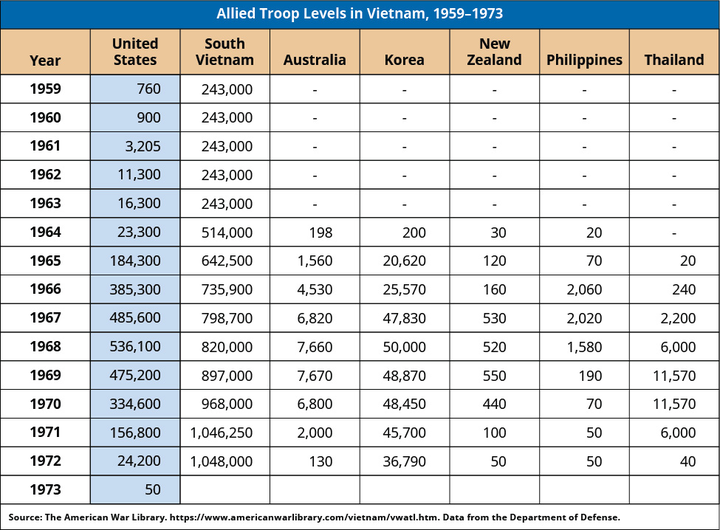

Allied Troop Levels in Vietnam, 1959-1973. (credit: “Allied Troop Levels in Vietnam” by Bill of Rights Institute/Flickr)

1. Which of the following was a direct result of the trend demonstrated in the chart?

- Increasing bipartisan support for the strategy of containing communism

- Strengthened alliance between Western democracies and the Soviet Union

- Growing support for a large nuclear arsenal

- Debates about the appropriate power of the executive branch to conduct military policy

2. Which of the following was a significant cause of the trend from 1963 to 1968 shown in the chart?

- U.S. support for noncommunist regimes

- Efforts to create a free-market global economy

- Public debate over the acceptable means of pursuing international goals

- Strengthening of the post World War II system of collective security

3. The military conflict in the area identified in the chart was most directly shaped by

- demographic change

- postwar decolonization

- détente

- rise of fascism

Primary Sources

Telegram From the Commander, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (Westmoreland) to the Commander in Chief, Pacific (Sharp), August 7, 1966. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v04/d205

Suggested Resources

Davidson, Philip B. Vietnam at War: The History, 1946-1975. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Hunt, Michael H., and Steven I. Levine. Arc of Empire: America’s Wars in Asia from the Philippines to Vietnam. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Krepenevich, Andrew F., Jr. The Army and Vietnam. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Moore, Harold G., and Joseph L. Galloway, We Were Soldiers Once And Young: Ia Drang, the Battle that Changed the War in Vietnam. New York: Random House, 1992.

Olson, James S., and Randy Roberts, Where the Domino Fell: America and Vietnam, 1945 to 1990. New York: St. Martin’s, 1991.

Prados, John. Vietnam: The History of an Unwinnable War, 1945-1975. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2009.

Summers, Harry G., Jr. On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War. Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1982.

Westmoreland, William C. A Soldier Reports. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1976.